Frances Goldin at City Hall with the Cooper Square urban renewal model.

Within a few months of arriving in New York in 1977, I met three extraordinary individuals who influenced the trajectory of my life in profound ways. One was my professor at Cooper Union, Joel Meyerowitz, who was a pioneer of color photography. The second was Jack Hardy, songwriter, and leader of the Greenwich Village folk scene. Hardy died seven years ago and I wrote an extended essay about him here. The third was Frances Goldin, the guiding force behind the Cooper Square Committee, a housing advocacy organization located on East 4th Street between the Bowery and Second Avenue.

Having begun my studies as an urban design major in the architecture school of the University of Virginia, the work of the committee was of particular interest to me. I was subletting an apartment in a city-owned tenement that was part of the Cooper Square urban renewal area, which covered a dozen blocks of the East Village, and as I discovered, was originally slated for demolition and replacement with low-income projects. It was a typical Robert Moses slash and burn initiative, the kind that had already reshaped the topography of extensive parts of the city. Moses’ bulldozers were kept at bay here, and his plan to run an expressway through Soho and the Lower East also came to a grinding halt, though not before dozens of buildings were torn down near the Williamsburg Bridge and thousands displaced. Those vacant lots stood empty for 50 years – a book could be written about the epic struggle over that site – until 2011 when an agreement was reached with the community to allow rebuilding.

Seward Park Urban Renewal Area in 1980 – photo © Brian Rose/Edward Fausty

One of the key figures in stopping these two projects was Frances Goldin. She and Jane Jacobs, who wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, were aligned in the fight against Moses’ freeway, and she and urban planner Walter Thabit came together to defeat Moses in Cooper Square, in part, by proposing an alternate plan that preserved the right of residents to return to any new housing built on the site. Jacobs’ simple idea – which at the time bucked conventional thinking – was that cities were just fine the way they were. That fine-grained neighborhoods were preferable to towers-in-the-park mega-developments, and ultimately, that people should come before infrastructure.

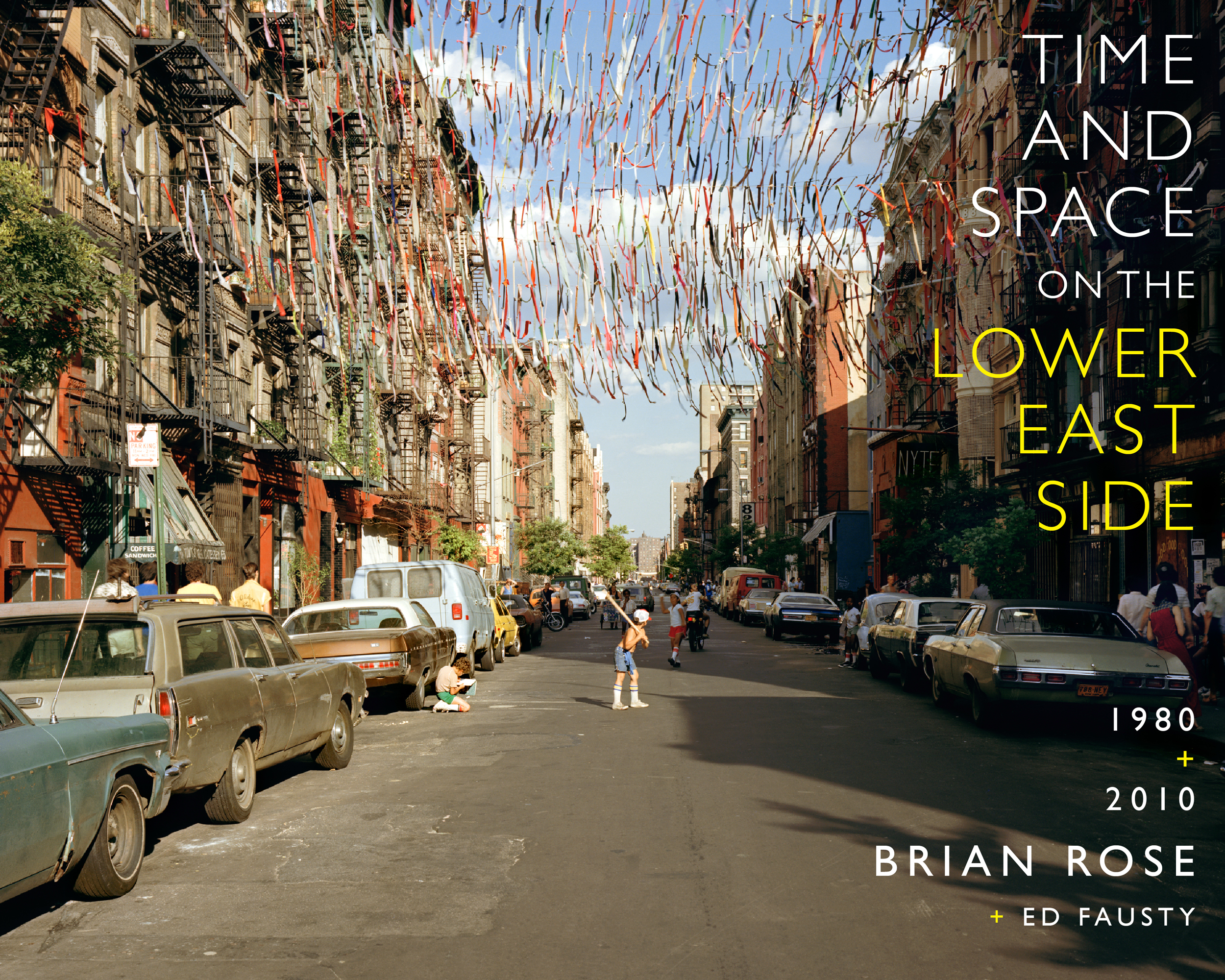

Cover of Time and Space on the Lower East Sode – East 4th Street 1980 – © Brian Rose/Edward Fausty

When I first got involved with the Cooper Square Committee I was perceived as a somewhat suspect outsider. Frances Goldin was 30 years older than I, a born and bred New Yorker, Jewish, and an openly avowed communist. I was a newcomer from Virginia, an artist attending an elite college, and while politically engaged, hardly sympathetic to an economic theory that had inspired ruthless dictatorships like the Soviet Union and China. On paper, this should not have led to a productive and warm relationship.

The fact that it did, I ascribe largely to Fran, who it turns out, welcomed everyone into the fold as long as you shared the same basic goals, which centered on preserving and creating affordable housing and organizing people against the powers that be. The way in which she assumed the role as spokesman for poor people of color sometimes gave me pause, but she never wavered in her commitment, and never gave anyone reason to doubt her sincerity. And as a result, she built strong bridges between ethnic groups, particularly with the large Latino community on the Lower East Side.

In 1980, when I joined Cooper Square’s steering committee, Walter Thabit’s alternate plan for the neighborhood was, to a great extent, moribund. Although it had survived multiple changes in City Hall, the free-flowing tap of money for housing from the federal government had slowed to a trickle, making new construction, which was a basic component of Thabit’s plan, unworkable. Following the lead of steering committee member Chuck Ritchie, I argued that we should shift our focus to preserving the existing tenement buildings and limiting new construction to the largely vacant sites on either side of Houston Street. One piece of the alternate plan was finally built at the corner of Stanton Street and the Bowery, but budget constraints resulted in a building stripped of almost all architectural merit. It was much-needed housing – and still is – but created a deadening presence on the street. It is a monolithic brick edifice partially set back from the street with no shops or “eyes on the street,” the opposite of Jane Jacobs’ concept of urbanity.

Cooper Square Urban Renewal Area 1980 – © Brian Rose/Edward Fausty

Eventually, the Cooper Square Committee hammered out a memorandum of understanding with the city green lighting new development on the largely vacant lots on Houston Street, and the rehabilitation of the tenement buildings on 3rdand 4th Streets. A quarter of the new development was subsidized housing, and when you added in the preservation of the existing housing, it came to almost 1,000 units of low-cost housing. In getting to that agreement, which was approved by Mayor David Dinkins, I participated in a series of difficult but ultimately productive meetings with Fran and city representatives. I was sometimes the lead negotiator for our side, but everyone knew that it was only with Goldin’s assent that things would go forward. I knew that she would never back down from our core goals, and the city understood that our strength as sponsoring organization lay in a highly engaged constituency and well-developed political alliances. Our power to negotiate was achieved by years of organizing and protesting – that was Frances Goldin.

But there was something else. Frances Goldin was inspirational. She was eloquent, charismatic, and brilliant, and that overflowing cornucopia of qualities made her a formidable presence. You could not say no to Frances Goldin. If we needed a spread of food for a meeting, she would go to Abe Lebwohl of the Second Avenue Deli and ask him to donate. He could not refuse. When she demanded that the city include a community swimming pool in the new development to replace one lost years before, the city could not say no. And when she demanded that the Liz Christy Garden at the Bowery and Houston be preserved, the city could not say no.

In 1987 a group of young Dutch students came to New York to study the effects of gentrification, which even then, was a hot topic. The students gathered in the Cooper Square office and Frances Goldin talked about the history of the organization, our achievements, and what we hoped to accomplish in the future. One of the students present was Renee Schoonbeek, who said that Fran looked out at the group and focusing her eyes on her said, “we need you to help us in what we are doing.”

That appeal resonated with Renee, who two years later came back to New York with her friend Josja van der Veer, to intern with the Cooper Square Committee. Together we worked on a plan to place all of the renovated tenement buildings into a mutual housing association, an innovative tenant coop designed to maintain low-cost housing into perpetuity. Key players in that effort were Val Orselli, long-time Cooper Square director, and urban planner Brian Sullivan. That organization continues to manage and maintain over two dozen apartment buildings.

Renee and I worked closely together for several months attending meetings that were often contentious and even dispiriting. But we persevered, and our relationship deepened. Renee, on a temporary visa, had to return to the Netherlands, and as I like to say, the separation failed. We were married in 1993, and Renee went on to become a successful urban planner, and we have a son Brendan who is studying journalism. Josja is now the head of real estate for the Vrije Universiteit (Free University) in Amsterdam.

I have no doubt that it was Frances Goldin’s entreaty to come help that brought us together.

Frances Goldin and I at an exhibition about the Seward Park Urban Renewal area.

One of the last times I saw Fran before her passing a week ago, I asked her if she felt that she, and we collectively, had been successful in our efforts. She said, “Yes, absolutely. We won.” She was right, but I was almost surprised to hear it from someone who believed that the fight was never-ending. She knew what she had accomplished, and I was gratified that at the end of her life she felt that sense of closure, even triumph. What a life, lived to the fullest.