Connecticut/New York

Anselm Kiefer: Velimir Chlebnikov, The Aldrich Museum

On Saturday, drove with friends Art and Eve to Ridgefield, Connecticut to see an exhibition by the German painter Anselm Kiefer who has created a huge multi-paneled piece inspired by the Russian poet Velimir Chlebnikov (1885-1922), one the founders of Russian futurism, the modernist art movement. To quote from the exhibit brochure: “He wrote poems and pamphlets that, through complex mathematical formulae, chart the ebb and flow of conflicts East and West, the creation of global communications systems, and the supposed existence of climactic naval battles every 317 years.”

A peek inside — photography not allowed

The thirty canvases have lead boats and submarines wired to their surfaces along with various bits and pieces of cloth tape, straw, and dead sunflowers. Kiefer designed the shed-like building to house the paintings, and the whole thing was transported from Germany to the garden of the Alddrich. The piece is actually on loan from an anonymous owner and will only be viewable until October 1. Why anyone would acquire such a gargantuan–not to mention important–piece for their personal enjoyment is beyond me.

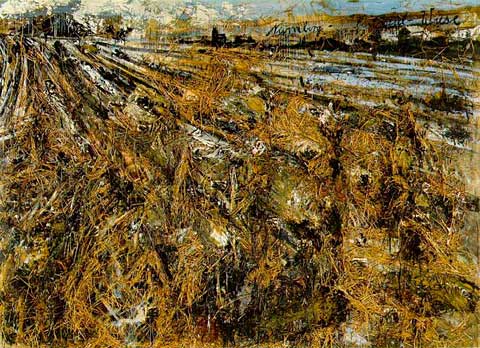

Nuremberg, Anselm Kiefer, 1980

Kiefer’s work has interested me for a long time. Back in the ’80s as I was beginning to photograph the Iron Curtain border, I saw Kiefer’s landscape oriented paintings at his gallery in New York. I then found these same haunted landscapes traveling across central Europe. I even wrote a song (mp3 file) based on the title of a series of Russian futurist drawings by Krutikov called Cities on the Aerial Paths of Communication, which was about the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of utopian idealism. I find myself attracted to the large themes that Kiefer grapples with so obsessively, though I pursue a less mythological approach.

Oebisfelde, Germany — the Iron Curtain, 1987 (4×5 film)

Grace Glueck of the New York Times writes of Kiefer: “he confronts the realization that civilization is still not a comfortable distance from chaos and may never be.”

New York/Connecticut

Since I left Amsterdam I’ve been been dealing with necessary business stuff, and continuing to work on my portfolio. I picked up the film shot in Berlin, and will post some of the images in the coming days.

On Friday I went up to Connecticut to visit friends Art Presson and Eve Kessler. I’ve know them both since the days when I worked at ICP (International Center of Photography) in the early ’80s. They have an outstanding collection of photography that I am pleased to be a part of. The prints hang all over their house in “salon style,” not always well-lit, but interesting for the unexpected juxtapositions of images. Most of the collection is comprised of black and white prints of modest size. Some of the images are well-known classics–like this one.

Kessler/Presson collection with Albino Sword Swallower by Diane Arbus

Amsterdam/New York

Brendan, my son, in front of the Silodam, our apartment building in

Amsterdam

Back to New York with my film from Berlin and the scans I’ve been working on for the past several weeks. These I will be printing for my portfolio. Had a brief visit from my sister, Cathy Rose, who was on her way to a two-week literary workshop in St. Petersburg, Russia.

In Amsterdam all eyes are on World Cup soccer–my Berlin pictures will, inescapably, include evidence of Germany’s hosting of the event. But I am happy to be heading back in the States in time to catch most of the NBA finals. I wonder if the Germans will be able to distract themselves from soccer long enough to see their countryman Dirk Nowitski lead the Dallas Mavericks to a possible title.

On a darker note, the Times of London ran a story today about how the site of Hitler’s bunker adjacent to the Holocaust memorial and Potsdamer Platz has been identified for the first time with a sign in German and English. The reason given for its previous anonymity has always been the fear that it might become a right wing pilgrimage place. I have always felt that history must be acknowledged rather than covered up. Visitors to Berlin come looking for the past whether it be traces of the Wall or vestiges of the Nazi era. The city’s willingness to finally acknowledge the bunker’s location is further evidence of Germany’s confidence in itself as it moves into the future.

Berlin/Amsterdam

Berlin

Day Four

My last day shooting in Berlin, the weather was tumultuous with dark clouds sweeping across the sky, sudden showers and gusts of wind. It ‘s the kind of day that can drive you crazy trying to manage the view camera and keep your wits about you. But it can also lead to moments of visual drama. Fortunately, Anamarie, my friend from New York–living in Berlin for many years–came along for moral support and help with my equipment.

We began, not by shooting, but by visiting several galleries on the Zimmerstrasse near Checkpoint Charlie, where the Wall used to run down the middle of the street. The building we went into was in East Berlin in those days. We stopped in Galerie Nordenhake and saw photographs by Esko Mannikko from Finland, someone I’d never heard of. The images were close-ups of horses and farm animals lit sharply with flash and printed in fairly contrasty saturated color. A number of the images focused on eyes, sometimes closed, sometimes open. At first glance I thought the images relied too much on the gimmick of tight cropping, but as I rounded the gallery I began to warm to them, and concluded that there was something deeply felt about the images. At the gallery desk I leafed through selections of the photographer’s other work, and found them equally compelling. Will watch for his work in the future.

On the outside of the gallery building, words were printed on a blank wall, one of many such surfaces exposed by the bombing of World War II. The words, in German, were quotes from a homeless man talking about his life situation. The show continued inside where there were videos of various homeless men accompanied by similarly printed quotes. The work was well-done, but I’ve always been wary of this kind of aestheticizing by artists, however admirable the intention.

Milovan Markovic – Homeless Berlin 2006, Zimmerstrasse

near Checkpoint Charlie

Most of the afternoon was spent photographing the Jewish Museum, the famous Daniel Libeskind building on Lindenstrasse. Up to this point I had never attempted to photograph the museum largely because it was not directly along the path of the Wall. But having finished the Lost Border book, I no longer felt constrained by previous limitations. The museum, of course, has been photographed by any number of serious architectural photographers and photo-journalists, so it was not my intention to add to that body of work.

When I first visited the museum the present exhibition had not yet been installed. The empty interior spaces, employing allegory and geometric abstraction, presented Jewish history as a harrowing experience . As pure structure, the museum functioned to a great degree as a Holocaust memorial. The exhibition, however, is a historical overview of Jewish life in Germany and attempts to show the richness of Jewish culture, not just its tragic aspects. Unfortunately, for me, the exhibition is at odds with the architecture of the building, and neither comes off very well. Libeskind’s echoing emptiness is stuffed with bric-a-brac. And the exhibit itself would have been better off displayed in conventional rectangular rooms.

But outside, the museum’s zig-zagging electricity remains as strong as ever, though its severity is somewhat softened by the lushness of the garden surrounding it, especially in late May. Most pictures of the museum don’t show the fact that it is located in a largely low income neighborhood of Kreuzberg. High rise towers with balconies festooned with satellite dishes indicate the presence of immigrants. The great irony of the Jewish Museum’s location is that it sits in the midst of a largely Muslim neighborhood.

Jewish Museum, Berlin with nearby low income apartment tower

In the landscape surrounding the museum, the cuttout lines and slashes of the facade are delineated on the ground as well. Steel rails vector away from the building. Except for a fenced section in the rear that presumably needed to be protected, the landscape appears borderless, filtering out into the neighboring parkland. I did several photographs that attempt to show this integration of landscaping, though I doubt that any will be wholly successful. Other pictures I made illustrate the closeness of the adjacent housing projects. Go here for Google satellite view of the Jewish Museum.

From there I headed back toward Checkpoint Charlie, taking pictures of interesting urban layering along the way. I did two pictures that include one of my favorite modern buildings in Berlin. The GSW building by Sauerbruch Hutton. At Checkpoint Charlie I had hoped to get a photograph of the crazy kitsch that now serves as historical monument to one of the most important and sensitive spots of the Cold War. The early ’60s checkpoint shed has been recreated complete with protective sandbags, and actors in American and Russian uniforms stamp tourists’ passports with phony East German day visas. But the street was in shadow, so I used my last sheet of film elsewhere. Go here for real checkpoint shed in 1987.

Berlin

Day Three

Once again I drove to Potsdamer Platz to begin the day. Not wanting to drive the car into Berlin Mitte where parking is difficult, I took the S-Bahn two stops to the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof. Before 1989 this was the most common way to enter East Berlin as a visitor. The other, more famous crossing, was Checkpoint Charlie. Friedrichstrasse was also the way out of East Berlin, which was generally impossible for people living behind the Iron Curtain. Retirees, and others with some special dispensation made it across, however. The glass customs hall next to the station was the scene of emotional farewells as friends and relatives returned to the west, hence it’s nickname, Traenenpalast, or palace of tears. Today, the building is preserved in somewhat shabby condition as a historic site, and it is currently being used as a music venue. I took several photographs of the building and surrounding area.

Traenenpalast (Palace of Tears)

From there I walked east below the elevated train viaduct stopping to make a photo or two, grabbing a currywurst at a makeshift beer garden across the street from the Pergamon Museum, and eventually reaching Unter den Linden in front of Schinkel’s Altes Museum, the Berliner Dom, and the partially demolished Palast der Republik across the street. I walked onto the Schlossplatz, the former site of the earlier Baroque palace, which was torn down after the war by the East Germans. The parade ground thus created was called Marx-Engels Platz and was primarily used as a parking lot for communist party functionaries. Across the Spree, Schinkel’s Bauakademie is being recronstructed–one corner of the building is complete–and the rest of the building’s volume is wrapped in a printed facsimile of the facade. I was quite taken by the trompe l’oeil effect. It was a cloudy day, but the false facade retained a permanently sunny aspect.

Bauakademie, reconstruction based on design

by Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Turning back to the Palast der Republik, I did two photographs showing the stripped frame of the building and an outdoor exhibition on the history of the site. Both the Prussian era Schloss and the Bauakademie survived the war–with damage–but could have been restored. The German Democratic Republic, short of money, and ideologically charged with cleansing the past, tore the historic structures down. Since the fall of communism, both buildings have been the subject of intense debates within the architectural community and among the public at large. The German parliament has voted to rebuild the pre-war Schloss, or at least some version of it.

Go here for an earlier photograph of the Palast der Republik.

Berlin

Day Two

Began the day at the Potsdamer Platz Starbucks. That should give you an idea how much things have changed in Germany. Not to mention the fact that Potsdamer Platz was a desolate zone of abandonement with the Wall running through it until 1989. And then reconstruction only began in the mid-90s.

The Platz was filled with soccer-related activities–the World Cup, hosted by Germany, is just a couple of weeks off–and on the horizon, the Fernsehturm’s ball-shaped top was decorated as a magenta and silver soccer ball. Magenta being the ever present color of sponsor Deutsche Telecom. I took a photograph of the Berlin Wall exhibit, comprised of wall segments and information panels, in front of one of the entrances to the Potsdamer Platz Bahnhof.

Holocaust Memorial

I then walked a short distance away to the Holocaust memorial, to be exact, the Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe. I understand the reasons for the name, but the chilling specificity of it guarantees that it will never be used by most visitors. I’ve already had a heated conversation with someone who did not apprehend nor appreciate the fact that the memorial excluded the Gypsies, homosexuals, and other victims of the Nazis. Whatever the matter, the memorial has become an enormously “popular” tourist destination.

I last photographed the site in 2004 when finishing up my book The Lost Border. At that time, it was mostly finished, but still fenced off. Visitors could climb viewing platforms for a better view. Now, the field of stone beckons one and all to wade in among the black slabs and descend into the disorienting grid. Children delight in the maze-like aspect of it, which is something architect Peter Eisenman anticipated. But he would likely not approve of the fast food outlets and souvenir shops that have been given residence along the eastern edge of the memorial.

I stayed at the memorial for about three hours taking pictures. Several people came up to chat. One elderly woman from the Netherlands who remembered Kristallnacht and all that followed soon after. The sun was intermittent, which meant I had to wait for long periods of time for the light, but the skies were filled with swiftly moving clouds. I spoke with one student photographer from Germany, and told him that I was not really photographing the thing itself, but rather what contains the thing itself. By that I meant the landscape versus particular objects or events, as well as my philosophical approach to looking at the world.

Berlin Wall Memorial, Marie-Elisabeth Lueders House,

Reichstag in the background

After that I walked past the Brandenburg Gate and Reichstag taking a couple of pictures along the way. I was interested in the new Hauptbahnhof, which was about to open that weekend, but with cloudiness and light rain I moved on. I crossed the Spree river and entered a Berlin Wall memorial in one of the government buildings. A number of slabs of the Wall had been erected in a large space following the trace of the former borderline. The slabs were painted with the numbers of people killed trying to escape across the border each year beginning with 1961 when the Wall was erected. The presentation was credited to the building’s architect, but I knew that the idea was taken from an earlier unofficial memorial done outside by Ben Wargin. Here is the original installation.

Berlin

Day One

I flew into Tegel airport, a hopelessly outmoded airport left over from the Cold War days, rented my car, and met up with my friend Anamarie at her house in Zehlendorf. It rained heavily all afternoon, so we went to the Martin-Gropius-Bau (museum) to see the Robert Polidori show. I have long admired Polidori’s architectural photography and have two of his books. There is a strong formal rigor to his compositions, which anchors the lush colors of old Havana or the acidy greens and purples of abandoned Chernobyl. This was the first time I’d seen his large prints–size being the rage these days–but appropriate, perhaps, for his work. The prints appeared to be conventional c-prints mounted on plexi or some other backing and then floated inside a frame. It is clear that the prints were made from digital scans, the tonal range often a bit unbelievable–shadows too open, highlights too closed, colors too saturated, separate surfaces too well delineated. Sometimes it gave his images a Vermeer-like photo-realism, which was enhanced in the Versailles pictures by the side light and glimpses of other rooms through doorways. But was this quality intentional? Would the prints have worked just as well with a lighter hand in Photoshop?

Polidori at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, large digital prints

The Martin-Gropius-Bau spaces were haphazardly lit, and I fought reflections constantly, but the older architecture of the galleries suited the images fine. I could have used fewer prints, however, and wish the exhibit had stayed exclusively with the Havana, Chernobyl, and Versailles images. Two extremely large images, digitally rendered more coarsely than the others, were completely unnecessary and should have been left out. I enjoyed the exhibit, despite the above complaints, but I prefer Polidori’s books and seeing his color spreads leap out of the black and white print of the New Yorker magazine.

Amsterdam/Berlin

I’ve been working pretty much every day on the scans I did in New York a few weeks ago. There are about 45 images all together, 15 each from New York, Amsterdam, and Berlin. The plan is to print these at 20×24 inches for portfolio purposes with a few, perhaps, at 40×50 inches. I will be working with Ben Diep in New York at Color Space Imaging to make the prints.

The Berlin series includes a few of the Lost Border pictures, but none from before 1989 when the Wall came down. A number of them were made in what was East Berlin and show vestiges of the former Communist regime. One picture was shot through the Iron fence in front of the Soviet embassy on Unter den Linden, a bust of Lenin staring outward. Another includes a large statue of Lenin standing on a traffic island in front of a large housing project. And I made several photographs of the Soviet war memorial in Treptow, a monumental assemblage of statues and stone sarcophagi with bas reliefs depicting the heroism of the Soviet Army. There are quotes by Stalin etched in stone, chilling to encounter in person. The memorial at Treptow still exists and is being actively maintained, but much of Communist East Germany has already disappeared. The Palast der Republik is presently being torn down (see pictures here on Flkr), and I have a photograph from the late ’90s that will be part of my Berlin series.

Communist era mural (4×5 film)

Another existing piece of pre-1989 history, a mural illustrating the supposed worker’s paradise of the German Democratic Republic, has been preserved in Berlin Mitte. My photograph was made shortly after the Wall came down. I also took some photographs of East Berlin before ’89, see below, but I found the experience unnerving, and felt that it was just a matter of time before I was detained by the East German authorities. So, I ended that mini-project after several days of work.

East Berlin, 1987, before the Wall came down (4×5 film)

Thursday I am flying to Berlin and plan to put in three or four days shooting. I no longer feel the need to stick to the former path of the Wall, though I will certainly retrace the line through the center of the city. I will see what’s left of the Palast of the Republik, and I am hoping to get a good photograph of the Holocaust memorial near Potsdamer Platz. I will also take a look at the new central train station recently completed near the Reichstag. Since I am traveling without a laptop, I won’t be able to post anything until after I return next week.

Amsterdam/Groningen

For the past few months I have been using the camera above, a wonderful pocket-sized digital camera. Despite my ongoing allegiance to the 4×5 view camera, I have been smitten with this baby camera with wide angle lens, and optical viewfinder (not shown in photo). I’ve been using it for this journal and taking it with me when going out with the view camera. It is a near perfect camera, but it has a few flaws, and one bit me the other day. The lens is retractable, which makes the camera completely flat when not in use. But when the lens is extended, it is not as solid as a lens with a fixed mount. While fiddling with it, the camera slipped off my desk and landed extended lens first. The lens mechanism jammed and would not budge. So, my current infatuation is off to the repair shop leaving me bereft and cameraless. I’ll be posting view camera pictures that I am working on in the meantime.

Tomorrow, I am headed to a small town near Groningen in the north of Holland for a family weekend outing. Next Thursday I will be traveling to Berlin with my view camera–and the Ricoh digital if it comes back from the shop in time.

Amsterdam/Borders

The Iron Curtain, 1987 (4×5 film)

As many of you already know, I recently published The Lost Border, the Landscape of the Iron Curtain, and most of the pictures from the book are also available on the Lost Border website. It is a project I began in 1985 when walls and fences traversed Europe dividing East and West. Subsequently, the Berlin Wall opened in 1989, Communism fell, and Germany reunified. The healing is incomplete, but it is ongoing, and in response to that I have continued to photograph the rebuilding of Berlin up to the present.

Today, the U.S. Senate voted to extend the barrier along the Mexican border an additional 500 miles. I do not pretend to have a solution to the illegal immigration problem, but I do know first hand the ugliness of walls, and that ultimately they fail to deter those who seek freedom. I also believe that such barriers become the recognizable face of countries–East Germany then, Israel and the U.S. today. These images are inevitably hard, if not brutal. It does not matter whether the walls are intended to keep people in or out. They are a futile response to conflicts that remain tragically unresolved. The construction of more walls and fences along the Mexican border is a sign of defeat.

Amsterdam/Ayaan Hirsi Ali

PARIS, May 15 — The Dutch government on Monday abruptly threatened to revoke the citizenship of one of the country’s most prominent members of Parliament, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Somali-born woman who arrived as a refugee 14 years ago.

–New York Times

I have never cared for Hirsi Ali’s politics, which I’ve found polarizing and self-aggrandizing. However, this is a political assasination virtually as despicable as the actual assasinations of Theo van Gogh and Pim Fortuyn. I am stunned.

Amsterdam/Texel

The weather remains unusually warm and pleasant here in the Netherlands. I am mostly working on the scans I did in New York, which will be printed for my New York/Amsterdam/Berlin portfolio. On Sunday we picked up Brendan, my son, from the island of Texel, on the North Sea coast. He was there visiting with his grandparents who have a house on the island.

Texel is the largest of the barrier islands along the northwest coast of Holland. Were it not for the dikes, it would consist primarily of a ridge of dunes. But there is a substantial hinterland behind the dunes with much farming, a few towns, and scattered vacation houses and camp grounds. The landscape is beautiful both in the dunes and on the flatland, and there are picturesque older farmhouses. But generally, the architecture is bland with lots of cheap brick and concrete. Despite the relative remoteness of the island–you can only get there by ferry–it is primarily a destination of middle class Dutch and German tourists, and to me, it lacks character. I’m sure the Dutch would argue with that.

Amsterdam

Back in Amsterdam, the weather was cold and wet for several days. But that has dramatically changed, and my studio is bathed in bright sunlight. The temperature is up near 70 degrees. Even though I place black foam board around my computer, it is difficult with so much light to work on images until later in the day–the evening is better.

Yesterday, I came home with my son Brendan, and a large group of Austrian architecture students were gawking at our famous building designed by the Dutch architecture firm MVRDV. Their teacher begged to let them see the interior, so I escorted them up to our apartment, and took them out to the large public balcony on the north end of the building. Although these were students on a field trip, it is common to see smaller groups of visitors engaged in the increasingly popular activity of architectural tourism.

New York/Blue

I’ve felt for a while that I needed to do more dusk and night photographs of the Lower East Side. The shop windows become more transparent as the sun goes down, and the street life changes as residents and tourists flock to the bars, restaurants, and clubs. Last night I went out at about 6, and did four photographs as the light faded. The first was of a nondescript new building–basic brick box with windows–at Stanton and Ludlow. On the left was a clothing shop, and to the right, a felt rope designating the queue for a club. It was early, so there were no standees. A bit further down on Stanton I photographed another clothing store, this time juxtaposed against a Chinese laundry.

I then walked down Clinton Street, which is a mishmosh of nail salons, convenience stores, fast food, and serious restaurants. Difficult to convey the diversity in photographs. I took a picture at the corner of Clinton and Delancey, a fast food restaurant on the left and the Williamsburg Bridge entrance on the right. As usual, when dealing with busy sidewalks, I found a spot up against a lamppost–any kind of street furniture will do– that people already have to maneuver around. This gives me a small piece of sidewalk I can stakeout with my camera and tripod.

At Norfolk and Delancey I made a photograph beneath Blue, the new apartment building designed by Bernard Tschumi, famed Swiss architect and former dean of the Columbia architecture school. No other building better epitomizes the changes occuring to the Lower East Side, or to New York for that matter. High style modern architecture meets the tenements and gritty streets of the city’s most important immigrant neighborhood. When Blue is finished later this year, my project will be complete.

New York/3rd Avenue

Another beautiful day, patchy clouds, 70 degrees. I decided to give some attention to the thus far neglected Third Avenue border of what I am defining as the Lower East Side. Old timers still think of it as part of the LES, but newcomers are likely to know it only as the East Village. Whatever the case, I began by walking uptown to East 4th Street where the Bowery turns into Third Avenue. I took a few pictures on 4th Street just to the east of the avenue, the block I lived on when I first moved to New York in 1977. At that time, the block was considerably more rundown, although the buildings were fully occupied, unlike the desolate area east of Avenue A. Extensive renovation has since taken place, and the storefronts have been rented out to an interesting hodepodge of small businesses.

Walking up Third Avenue I noticed that demolition was taking place on several old buildings between 5th and 6th Streets, a new residential tower the likely replacement. I stepped into Cooper Square Park and made a picture looking toward that block, and then another shot looking further north with the Cooper Union Foundation Building rising up on the left. The low rise Cooper Union building across 3rd Avenue is scheduled to be replaced by taller glass structure by Thom Mayne of the LA architecture firm Morphosis.

At St. Mark’s Place with its cacophanous jumble of cheap shops and restaurants I did a photograph from within the fenced outdoor seating of Starbucks, one of three such coffeeshops in the same number of blocks. An employee informed me that photography was not allowed, but I had already gotten my shot, as well as a frappacino. The tables were full of people enjoying the warm afternoon, dozens of people streamed by on St. Mark’s, and I leave it to the observer whether to interpret the scene as idyllic urban street life, or as further evidence of the cultural decline of the neighborhood.

Back in 1980 the stretch of Third Avenue between St. Mark’s Place and 14th Street was a distinctly uninviting area with a series of parking lots known for harboring prostitutes and drug dealers. Today, the parking lots have been filled with NYU dormitories, and at least two new apartment buildings appear in the offing. I walked down Stuyvesant Street with its distinguished row of early 19th century houses, and made a photograph of one facade draped with wisteria, the spire of St. Mark’s Church in the background. I then entered the churchyard of St. Mark’s and took a couple of photographs that included the columns and statues at the church entrance.

Walking back to Third Avenue, I made a right on 13th Street and stood opposite a large vacant lot with two construction trailers nearby. No signs indicated the apparent future development of the site. I climbed the stairs of a tenement, and did a wide shot of the lot with the buildings of 14th Street rising up beyond. From there I trudged up to the lab on 20th Street and dropped off my film.

New York/Chinatown

After several mostly wet days, and lots of work on the computer, I returned to shooting on the Lower East Side. I took the subway down to City Hall, and walked along the approaches to the Brooklyn Bridge, the southern boundary of my project. At Front Street I noticed Photographic Gallery, ducked in briefly, and saw a show called “Unembedded,” photographs taken in Iraq by photojournalists who were not part of an official embed with U.S. forces. These are the kind of pictures rarely seen in American media both in their graphic depiction of the violence and in their attention to the lives of Iraqi people. I must confess to being jaded by the ubiquitous clichés of photojournalism. This group of photographs, while well-seen, does not avoid the familiar visual devices. On the other hand, these are courageous photographers who are trying to communicate the reality of the war, and I commend them for the effort.

Just down the street from the gallery I photographed the Brooklyn Bridge from an angle I recall vaguely shooting 25 years ago. Below the on/off ramps looking up to the stone tower on the Manhattan side. From there I walked out to the landscaped esplanade beneath the bridge, which did not exist in 1980. The immediate neighborhood is the former Fulton Fish Market now decamped to the Bronx. It’s another example of the gradual loss of rough and ready work from the island of Manhattan.

Smith Houses and Brooklyn Bridge ramps

I did another photograph looking up through the bridge ramps toward the Alfred E. Smith houses, one of the chain of vast urban renewal projects lining the East River. These once forbidding forests of towers have become far less intimidating in today’s New York. In this case, the buildings looked reasonably maintained, and the grounds had been freshly re-landscaped. I then walked uptown toward Chinatown where I would spend the rest of the afternoon.

Chinatown is a major subject all on its own, but in 1980 it seemed somewhat peripheral to the rest of the Lower East Side, so I didn’t focus on it. In the intervening years it has greatly expanded north and east taking in the old Jewish enclave along Eldridge and Forsythe on up to Delancey Street. As I recall, Chinatown once seemed an exclusively pre-modern expression of Chinese culture. But now, a cadre of hip young Asians mixes with the older generations. In the playgrounds, basketball has become a popular Asian sport, no doubt inspired by the success of Yao Ming of the Houston Rockets.

I did several photographs along Madison Street next to the Al Smith Houses and then moved north under the Manhattan Bridge. One particular ensemble of buildings was striking with strangely juxtaposed architectural types spanning almost 150 years. There is, of course, a whole world of photographs that could be taken within and about Chinese culture in New York. What is of interest to me is the way in which, over the decades, different ethnic groups have recycled the same streetscapes, the same buildings, adding and subtracting structures, each leaving its stamp before moving on.