East 13th Street and Avenue B (4×5 film)

Spring is slowly arriving in New York. But on the Lower East Side spring blooms all year, at least at the community garden at East 13th and Avenue B.

New York/IAC Building

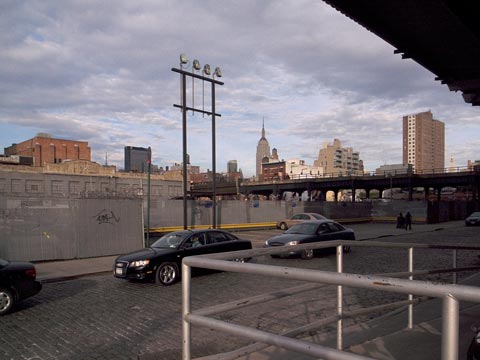

West Street opposite the meatpacking district

Yesterday, I walked again with my view camera up to Chelsea to photograph the IAC building, the first Frank Gehry building completed in New York. It’s fun for me to do this kind of thing when there’s no client breathing down my neck, and I can take things as they come. A few days ago I approached the building from the east, which one glimpses between existing brick warehouses and old factory buildings.

The High Line cuts through the city along 10th Avenue, and its transformation into an elevated promenade is already well underway. This strip is rapidly turning into the most stylish area of Manhattan with art galleries and cutting edge architecture. At the moment, there is a certain happy tension between the gritty desolation of vacant lots and the encroaching chic and sleek.

This time I approached the IAC building along West Street where it faces the Hudson River and the vast Chelsea Piers sports complex. As I’ve noted before, the building has the appearance of ship in full sail, its folds and pleats suggesting a southward heading. I’m not usually enthusiastic about such literal references in architecture, but I think in this case, the representational imagery is sufficiently abstracted formally.

The snow-white fritted glass has been disparaged by some as better befitting a suburban office park, but I find the crystalline folds and fragments of the curtain wall quite beautiful. That said, this is not one of Gehry’s most ground-breaking efforts. It is, however, an elegant, urbane, building that dares to sashay in a town more prone to marching, at least architecturally speaking.

New York/Apartment

New York/Chelsea/LES

The High Line under construction

I walked up to Chelsea by way of the Meatpacking District (Gansevoort Market), the formerly gritty meat market inhabited by bloody-aproned butchers and meat cutters as well as transvestite prostitutes. The area is now the epicenter of New York cool. The beautiful people wobble about on the cobblestones, and edge their way around the slabs of meat still hanging from hooks in front of the handful of remaining meat businesses. Like the Fulton Fish Market, New York is rapidly losing another piece of raw open air commerce. And like Soho, the area is destined to lose its buzz,though it’s hard to imagine where else the buzz can go in Manhattan.

One of the remaining meat businesses in the Gansevoort Market

For the time being, the Gansevoort Market and the Chelsea art district possess the kind of urban contrasts that I love to photograph. The High Line–the derelict elevated rail line–is under construction at the south end, and various buildings are going up around and literally over it with one structure straddling the viaduct. Of great interest is the almost finished IAC building designed by Frank Gehry. It’s Gehry’s first New York project, though there are numerous now in the pipeline.

I’m fond of the building, not exactly in a critical sense, but in the way this white glass apparition emerges from its neighborhood of mostly brick warehouses. Since it will undoubtedly be photographed by other accomplished architectural photographers, I’ve decided to look at the building in a more contextual way, not worrying so much about definitive signature views. I also know that as the neighborhood changes, and more projects fill the large gaps that surround the IAC building, the building will no longer float so aloofly above the fray. Like many fine buildings in New York, it will be come part of the furniture. I spent several morning hours working the east side of the building poking around parking lots and openings between buildings. My intention is to return for afternoon views later this week.

In the afternoon I took the L train over to the East Side and picked up again on photographing the Lower East Side. I walked across East 13th Street down Avenue C and over to Avenue B at Tompkins Square Park. I did several street views, and then spent almost an hour in the Campos Community Garden at East 9th and Avenue C. The trees were just beginning to show a hint of green. The morning began with a dynamic mixture of sun and clouds, but by later in the afternoon, the sky cleared, and the temperature soared almost to 65 degrees.

New York/Hudson Street

New York/Voices in Conflict

On Sunday I fetched the paper as usual, turned to the Metro section as usual, and was surprised to see a photograph of James Presson, the 16 year-old son of good friends of mine, along with two other students from Wilton High School who have created a play about Iraq told primarily through the voices and writings of soldiers and their families. The principal of the school, Timothy Canty, has blocked the production of the play, Voices in Conflict, because of the complaint of one parent, who believes the play is biased. I don’t know how the story was picked up by the Times, but given that Wilton is a well-heeled community with lots of movers and shakers in the New York area, it makes sense that something like this would filter out. The story was quickly picked up by several blogs, most notable Firedoglake, which recently dominated the coverage of the Scooter Libby perjury/obstruction of justice trial.

Jimmy, as you might well imagine, is an outstanding person, the kind of student that schools should be encouraging not quashing. He’s destined to do great things, despite weak-kneed people like Canty. I’ve been there myself–back in the early 70s–at the end of the Vietnam War when I ran for student council vice president of Walsingham Academy, a Catholic school in Williamsburg, Virginia. My views about things didn’t sit well with the principal, a nun who did not understand what was going on in the school, or the outside world for that matter, and felt threatened by outspoken students like me. Never mind the fact that I was a good student, and a starter on the basketball team. I had to be taught a lesson.

One morning the entire upper school was called into the auditorium for an unscheduled assembly. The principal and vice principal then proceeded to denounce my campaign literature as well as things I had written in the school newspaper without actually mentioning my name. This shocking vilification, which to this day wounds me deeply, went on for at least a half an hour before we were sent back to our homerooms to begin the school day. I went home that evening unable to explain or discuss things with my parents who were largely clueless about what went on at the school. However, one of my teachers, Mrs. Johnson, called and told them what at happened, and said that they should feel proud of me. Mrs. Johnson, as U.S. government and social studies teacher, instilled in me a profound respect for the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, the very things that are endangered today by the criminal cabal that led us into Iraq.

It’s obvious that Jimmy Presson has lots of support, and it’s coming in from far and wide. But he still has to walk into a school where, as I understand it from him, enthusiasm is tepid. For example, the student body president said in a post on the Voices in Conflict website: In fact, there is a very large portion of the students who support the principal, since for the most part he has only helped us out with our endeavors in the past. I do not know if any of you are school administrators (I certainly am not), but you should probably respect the fact that you get a lot of critisism (sic) for your actions. If this had gone the other way, Mr. Canty probably would have been the target of the voiced opposition (the family with the son in iraq). When it comes down to it, I do not know if his call was the right one, but it was his call to make. Please don’t think that I as a president don’t care how my students feel, but I cannot simply go in favor of a militant minority as opposed to an apathetic majority.

Please support the minority.

NY Times article

(registration required/fee after two weeks)

Voices in Conflict website

Other media links listed there

Firedoglake blog discussion

New York/Walking the Beat

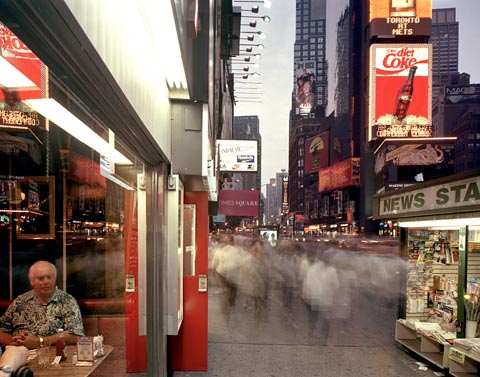

Times Square (4×5 film), late ’90s

I’ve been reading Adam Gopnik’s most recent collection of essays, some previously published in the New Yorker, Through the Children’s Gate. After returning from two years in Paris, he rediscovers New York, especially as seen through his children’s eyes. In one essay he finds himself on school safety patrol and in the process sees the block he’s assigned to in a totally different way–a much slowed down more richly detailed place.

It’s an experience I’m familiar with moving randomly down the street with my view camera sometimes taking several hours just going a handful of blocks. One becomes aware of a countless small things that are invisible when flowing with the crowd in the street or whizzing by in a taxi or bus. As Gopnik writes: “Density reveals itself as a particular pattern of parts: this odd little auction house, and this garage entrance beside it, and the two rival rental-car offices anchored by the garage, and the tailors down the stairs into this basement, and the Chinese restaurant that no one ever seems to enter or order from two doors away.”

In the slowed down world seen by few–the cop on the beat, the mailman, the photographer–the city seems suspended, still, the rushing pace of everything else blurs by and one becomes aware of a face, a figure, a buzzing neon light, the denizens of the block, the intimate moments held within the great rushing of sight and sound. Something, it would seem, is about to happen, a latent meaning suggests itself, then vanishes.

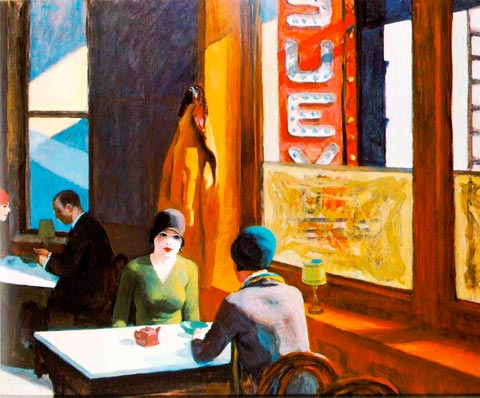

Chop Suey, Edward Hopper, 1929

Gopnik: “On one street, a thousand small efforts at making a living, none seeming obviously to thrive; all, in fact, to a single policeman’s passing eye, as empty and soulful as a Hopper afternoon interior, and yet it works. Somehow it thrives. (What Hooper was showing, it occurred to me, was not the desolation but the energy of American life: This is what capitalist city looks like most of the time, half asleep and waiting.)”

It’s always a question, what is it I am up to out there with my camera? When I was a student shooting 35mm slides I alternately went with the flow of the street and fought against it until I tied myself in knots with the exercise. It was color on color, pattern on pattern, light and dark, gesture juxtaposed against gesture, people in motion, everything stretched to the limit across the frame of the camera. I look back and there’s an exhilaration in it all, but I can also see where I had to stop, regroup, and think about why. It was then that I began working with the view camera. I had to slow down.

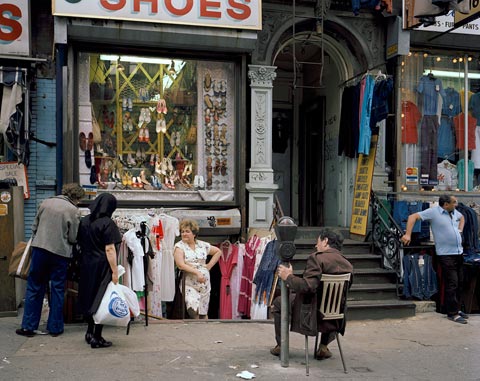

Orchard Street (Fausty/Rose 4×5 film) 1980

Gopnik: “That tone cops have–that steady wariness, even if you ask them for something simple and innocent, directions or advice–is the product of their experience. There really are sinister jigsaw-puzzle patterns out there, and you may be one of the pieces. This is why cops, so to speak, examine your edges even as they answer your entreaties.”

To me as a photographer it’s also about examining the edges, taking nothing at face value, recognizing the patterns, and walking the beat.

New York/The Lives of Others

The former Leninplatz in East Berlin, 1990 (4×5 film)

I saw The Lives of Others today sitting in a sparsely-filled midday showing at the Angelica on Houston Street. The movie, which recently won the best foreign language Oscar, is a deeply felt psychological thriller about life in the German Democratic Republic (DDR/East Germany) before the Wall came down. Much has been written about the film, the superb acting, the compact well-told story, and the clear laconic directing style of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck. So, I will confine my remarks to visual elements.

The Lives of Others is first and foremost about the interplay of the characters, and the story, it seems to me, could as easily be adapted for the stage as for the screen. That is not to say that the setting, both the exterior views of Berlin, and the interior views of apartments, are unimportant or not well-photographed. But the streetscape is glimpsed–often effectively–rather than lingered on. Although much has changed in Berlin in the 17 years since the collapse of the communist regime, there are countless streets throughout the former East Berlin that still feel, at a glance anyway, frozen in time. There are scores of buildings still pock-marked from World War II shrapnel, and vast tracts of DDR era housing remain at the edges of the city. Finding appropriate locations for the film did not require much recreation.

Prenzlauerberg, East Berlin, 1987 (4×5 film)

In the film, the writer Georg Dreyman lives in a commodious Berlin apartment at the top of a turn of the century walk-up, much like others I’ve seen, in Prenzlauerberg. The Stasi agent Gerd Wiesler lives in a sterile high rise like the one shown above on Leninplatz. In one scene, Dreyman and a couple of dissident artists stroll through a Soviet war memorial in Pankow in order to converse out of earshot of the Stasi. I photographed a similar Soviet memorial in Treptow in 1990. The film shows nothing of the Wall’s quick demise, the rush of people through it on the night of 9 November 1989, but it’s easy to spot the grafitti-plastered buildings of post-Wall Berlin, and the odd mix of western and eastern cars that shared the streets for several years.

Soviet war memorial in Treptower Park, Berlin, 1990 (4×5 film)

I had one brush with the Stasi when photographing Berlin in the ’80s. My friend Anamarie Michnevich and I–both interested in early modernist architecture–were poking around East Berlin looking for a particular housing project. I was carrying my view camera. We were confused by the map we had–the housing didn’t seem to be there–and suddenly I realized that we were standing adjacent a large complex of camera studded buildings. Suddenly, a voice called out and uniformed guards started approaching. We quickly retreated down some nearby steps into the subway, a train pulled in, and we were whisked away. Later, I found out that we had unwittingly stumbled upon the notorious Normannenstrasse headquarters of the East German secret police, the Stasi.

New York/Midtown

Seagram Building and Alexander Calder Sculpture

Aside from it’s architectural importance, the Seagram Building (designed by Mies van der Rohe), has personal significance to me. When I graduated from Cooper Union and began photographing the Lower East Side, the first prints I ever sold were to the Seagram collection. Phyllis Lambert of the Bronfman family, which owned Seagram, was putting together a collection of materials–including photographs–to serve as the basis for the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Acting on her behalf was Richard Pare, a curator and architectural photographer, who I had studied with at Cooper. Richard, along with Joel Meyerowitz, who also taught at Cooper, influenced my ideas about photography, especially with regards to the view camera. The money I got from that initial sale kept the Lower East Side project alive and launched my career, such as it is. I remember walking into the Seagram Building with my portfolio–and a good deal of satisfaction.

Bergdorf Goodman/58th and Fifth Avenue

LVMH building and Tourneau shop on 57th Street

In recent years, architecture has gotten more adventurous in New York, though it is still a relatively conservative town compared to any number of European capitals. One of the buildings to break the ice in the late 90s was this small tower by Christian de Portzamparc, the French architect. Its folded curtain wall disrupts–without violating–the continuous masonry and stone of the north side of 57th Street.

New York/Midtown

New York/In the Land of Meta

Houston Street between Sixth Avenue and MacDougal

It’s a losing proposition writing anything about Jeff Wall at this point. The juggernaut of critical approbation along with Wall’s own avalanche of supporting text is more than a puny photographer like me can withstand. I find myself standing on the corner of Houston and Sixth Avenue gazing up at the Jeff Wall billboard “Only at MoMA” and I feel weak and useless. Wall is a greater photographer than all others because his photographs aren’t just photographs, but containers of the entire canon of western art. They were made in response to a crisis of conceptualism that stymied us all. Wall triumphed. The rest of us stumbled blindly in the street trying to find lost things, places, ideas, rather than reinventing the medium, turning the act of photography inside out, like he did, creating hermetically sealed environments of almost reality, hyperreality, staged reality, photographs about photography, frozen like the little explosion of milk referring to nothing and everything.

New York/Green-Wood Cemetery

Civil War Soldiers’ Monument, Green-Wood Cemetery

I’ve been pretty busy this week doing architectural shoots, but today I went to the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn to meet and talk with the organizers of an exhibition about the Civil War and New York. I may do a series of pictures for the exhibit. I did a few snapshots, one here of the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument, which was erected shortly after the end of the war. It stands on a promintory overlooking the skyline of Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty.

New York City is dotted with some of the great sculptures of the 19th and early 20th centuries by such artists as Saint-Gaudens and Frederick MacMonnies. It’s an underappreciated aspect of the city, and many of the best pieces are virtually unknown to the public. Some are partially obscured by trees. Some are in plain view, but in difficult environments. One particularly unfortunate incident was the moving of the MacMonnies statue of Nathan Hale from the sidewalk of lower Broadway to a relatively inaccessible location within the City Hall gates.

Nathan Hale, old location on Broadway (4×5 film)

Hale stands on his pedestal in defiance, shirt open at the neck. His limbs are bound, but his pose says “take me.” The buoyancy of the sculpture is remarkable, as if Hale might leap from his perch if freed from his ropes. Above all, it’s an erotic tour de force–even homoerotic–now standing across from the steps of City Hall.

Although many people undoubtedly regard these traditional sculptures as out of touch with modern taste, there are some that remain fixed in the public’s imagination. One is the George Washington equestian statue in Union Square Park by Henry Kirke Brown. After September 11, the statue became the focal point of a spontaneous memorial to those who lost their lives in the Twin Towers. Intentional or not, this depiction of America’s first president became symbolic of the indefatigability of New Yorkers in this moment of great trial.

Union Square Park, September 2001 (4×5 film)

Unfortunately, this image of dignity and steadfastness competes with the public art across the street–Metronome–by Kristin Jones and Andrew Ginzel.

New York/Virginia

University of Virginia, me and my father

Whenever I vist Williamsburg, Virginia–where I grew up–I always think about the presence of architecture exhibited in the mostly modest structures that were built there in the 18th century. The way in which ideas of a new civilization were carved into the wilderness. The most important of Virginia’s early architects was, undoubtedly, Thomas Jefferson. He did not build anything in Williamsburg, where he served in the House of Burgesses, the parliament of colonial Virginia, but carried his ideas west to his own home, Monticello, the Virginia State capital in Richmond, and ultimately, the University of Virginia campus. Both my father and I went to UVA, and though I didn’t complete a degree there, I know the place well.

Upon returning to New York, I came across the American Institute of Architects poll “America’s Favorite Architecture,” and was shocked to find Jefferson’s campus missing from the 150 buildings listed–as was Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute in California, but that’s another story. I have traveled fairly widely, at least in Europe and the US, and have seen many of the world’s significant structures. Sometimes, I have had to warm up to certain buildings, walk around them, go inside, approach from different angles. As an architectural photographer I tend to stalk buildings, creep up on them, or try to surprise myself with an unexpected glance of the familiar. But sometimes, a building or a place will thrill me the first time around: the Parthenon, Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel, Wright’s Falling Water (also not on the list), Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower, Rockefeller Center, Gaudi’s Casa Mila, just to name some prominent ones.

After having seen all these other great buildings I still find Jefferson’s “academical village” one of the purest expressions of conceptual idealism in the world. Its design elements quote Roman and Greek classicism–the Rotunda is directly based on the Pantheon–while the organization of the space encourages the democratic interaction of professors and students. On the one hand, the space of the lawn creates an embracing enclosure, and on the other hand the lawn’s expanse leading to a view of the adjacent mountains opens this sanctuary of learning out to the world. The open end of the lawn was misguidedly closed off years ago, but the overall effect is only partially diminished.

I was not surprised to find that Americans favored older buildings, important icons, and emotionally or politically charged symbols like the World Trade Center. I, too, would place the Empire State Building up high on my list. But to completely miss what is arguably the greatest architectural work on the continent–among the finest in the world–designed by Thomas Jefferson, writer of the Declaration of Independence, is just unthinkable.

Virginia/Jamestown 1607-2007

Captain John Smith statue, Jamestown, Virginia

The last few days I was in Williamsburg, Virginia to visit my 85 year old father who remains active despite the usual infirmities that come with a long life. We spent one day touring Colonial Williamsburg, and another at Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America. This year is the 400th anniversary of Jamestown.

The most famous and important of the Jamestown settlers was Captain John Smith, whose colorful life is chronicled on a panel beneath his statue overlooking the James River. Whether Pocahontas actually saved Smith’s life, as he claimed, or not, the known facts of his 51 years as soldier, slave, explorer, and leader are impressive enough. Adjacent to the Smith statue is the recently discovered footprint of the original Jamestown fort, and just beyond, the tower of the 17th century church with its rebuilt sanctuary. Inside is a plaque, placed in 1959 by the Virginia State Bar, that speaks powerfully to the present, and the chipping away of liberties once thought sacred.

The text of the plaque refers to the Magna Carta and Common Law, which served as the basis for the American constitution and Bill of Rights. The principles of Common Law include the right to habeas corpus, due process, and the right to a jury of ones peers.

The last line of the plaque above reads:

Since Magna Carta the Common Law has been the cornerstone of individual liberties, even as against the crown, summarized later in the Bill of Rights its principles have inspired the development of our system of freedom under law, which is at once our dearest possesion and proudest achievement.

New York/Ground Zero

I took an exploratory walk with my view camera around the World Trade Center site today. It was in the mid-20s and icy underfoot, but the air was clear and sharp. I hadn’t been down there with my camera since just after 9/11, on Broadway, the first day they let people get that close. It was rough going that day trying to set up a view camera among thousands of jostling people–all with cameras, of course– but I got a couple of good photographs.

Broadway, September 2001 (4×5 film)

At one point I stepped off Broadway onto a side street away from the crush of gawkers. A man walked up carrying a single digital camera, no camera bag as I recall, and he asked me if I was a documentary photographer. I said yes, more or less. I looked at him more intently, and then said, you’re James Nachtwey aren’t you. He said yes. Later that week I saw his extraodinary pictures of the scene in Time magazine.

After that, Joel Meyerowitz got access to Ground Zero and made the photographs that are now published in an oversized book called Aftermath. I had no press pass or special access, so I left the subject alone except peripherally in images made in other places. Now that the big boys have left for other photographic battlefields, maybe it’s time for me to do what I have always tried to do–take a longer, more patient, view of history.

New York/The F Blog

Tippelzone (prostitution zone), Amsterdam (4×5 film)

A few months ago I was invited by Joakim Sebring of the F Blog, a weblog on photography maintained by a group of photographers based in Sweden, to submit a series of my pictures of Amsterdam. It took me a while to get the portfolio together, but I have now finished a new batch of scans of my Amsterdam work. The photographs and short essay can be found on the F Blog. It looks great. Thanks, Joakim for the opportunity.

Here’s the part of the essay that goes with the photo above:

Among the strangest sights on the periphery of Amsterdam was a fenced in drive surrounded by a sidewalk and a dozen bus shelters—also situated along a rail viaduct. During the day it was deserted. At night cars circled the drive as men ogled the women standing in the shelters. This was Amsterdam’s official prostitution zone (tippelzone), an attempt to regulate drug-addicted prostitutes and remove them from the center of town. The attempt failed for a myriad of reasons, not the least of which was the admission by a prominent city councilman that he frequented the zone. The tippelzone closed in 2003, but the paved circuit and bus shelters remain.

New York/Toys in Brooklyn

Toys in Brooklyn

We spent the weekend visiting friends in Brooklyn, shopping at the Strand bookstore, playing and helping with Junior Knicks basketball at the Y. But through it all I could never push out of my mind the war in Iraq, the President’s “surge,” and the sabre rattling aimed at Iran. The Times ran an editorial today about William Butler Yeats’ poem The Second Coming relating it to current events. The poem was written at the end of World War I at a particularly bleak point in history, and I can’t help but feel we are on the verge of slipping into our own era’s senseless world war–call it World War III. Who will rise to stop this insanity? As Yeats wrote, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

New York/The Snow of Yesteryear

Orchard Street, New York City, February 11, 2006 (4×5 film)

It’s been cold in New York City of late, but no snow. Upstate there’s 10 feet or more of the white stuff. Here it’s been dry as a bone. The Hudson is partly frozen over, but no snow. People talk about the snows of long ago, historical winters undisturbed by the spectre of global warming. Just a quick reminder. I took the photograph above exactly one year ago on Orchard Street on the Lower East Side. 26.9 inches. The largest single snowfall in New York City history.