My wife and son survey building designed by Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Two weeks ago I visited Bronx Community College, originally the uptown campus of New York University. The main quad is anchored by a symmetrical grouping of neoclassical buildings by Stanford White, the designer of many New York buildings from the turn of the 19th century including the now demolished Penn Station. Behind White’s Gould Library is the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, which I wrote about in a recent post.

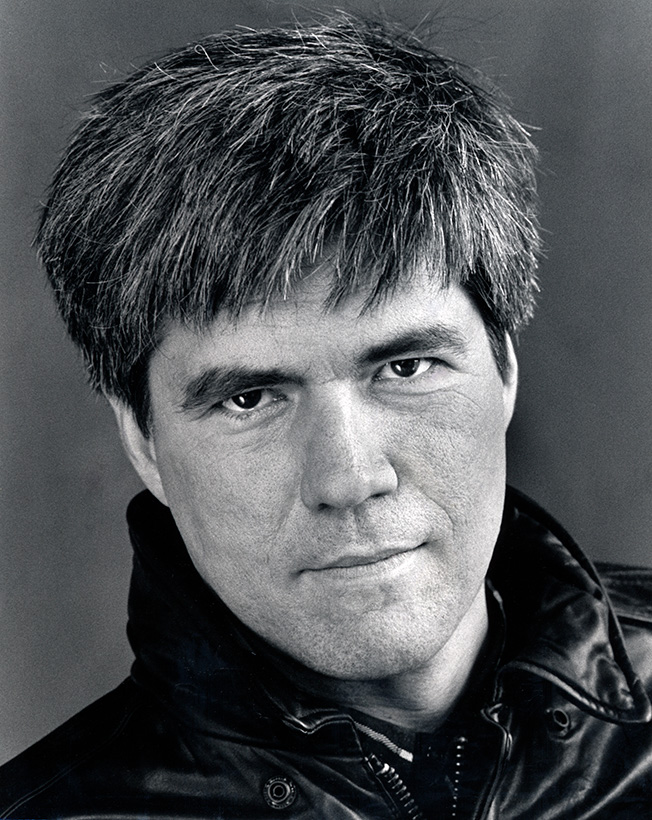

Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

In 1956, NYU hired Marcel Breuer to create a new masterplan for their University Heights campus. Breuer, a Bauhaus trained architect, who left Nazi Germany in the 30s, worked in a style now called Brutalism. The name came from the French, beton brut, which refers to raw concrete. At NYU, he combined expressive form with utilitarian bands of bricks and glass, and throughout, there are low stone walls, not unlike those used in local farmer’s fields.

After visiting the Hall of Fame, we first encountered a classroom building with a swooping concrete entrance canopy, similar to Breuer’s UNESCO headquarters in Paris. I climbed the hill adjacent, topped with a decrepit war memorial — utterly neglected. Dozens of window air conditioners disrupted what was once a clean uninterrupted composition.

Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Walking past this building we arrived at terrace with a low horizontal building and freestanding trapezoidal structure known as Begrisch Hall. It contains an auditorium, which is accessible by a pedestrian bridge. The streaking in the concrete above is not intentional — the entire complex is in shamefully bad condition.

Begrisch Hall, Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Begrisch Hall has been named an official city landmark, but as far as I know, not the entire ensemble of buildings. As I walked on further, I became more and more astonished and dismayed. It was like stumbling upon a lost archaeological site, crumbling, yet mostly intact. Of course, it is right here in the Bronx, perched high up over the Harlem River, chosen because of its prominent location.

Completed University Heights campus. “Now, the University will no longer be hidden under a bushel, but will be set on a hill-top and there will be not the slightest doubt as to its existence in the mind of anyone who passes University Heights.”

– University Quarterly magazine, 1894

But NYU at University Heights did not become another Columbia or Fordham University flourishing outside the center of Manhattan. Lehman College to the north, however, which also has two Breuer buildings, remains a thriving campus.

Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

And then around the corner, another amazing sight. Two bridges supported by concrete pillars lead to a slightly curved dormitory building, set down the slope of the hillside. No air conditioners here, but there are vents in the brick banding, and the window glass and mullions seem heavier than what was likely there originally.

Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

From here we walked back to the quad and stood opposite Meister Hall, which we had passed by on our way to the Hall of Fame. All four walls of the quad have been completed with the recent addition of a library designed by Robert Stern. It attempts to bridge the gap between Stanford White’s Pantheon-inspired Gould Library and Breuer’s vigorously modern Meister Hall — and in doing so it falls somewhere, or nowhere, in between.

Tech II (Meister Hall), Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Meister Hall was originally named Tech II, and in 1970 it was the last of the Breuer buildings to be completed on the campus. It housed the university engineering and science departments. There is a clear distinction between the elevator and stair towers with yellow brick matching the earlier campus buildings. Along the street a low structure is raised up on concrete feet with the main body of the building set a distance behind. Between the two structures was a courtyard with paving stones. It all felt very European to me — France, or perhaps, Italy.

Tech II (Meister Hall), Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

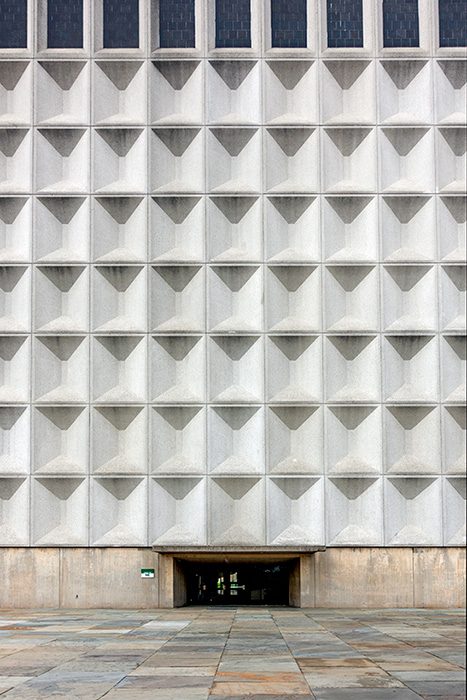

As someone who has photographed New York extensively in all five boroughs, I know the city better than most, and its urban landscape continues to provide fresh surprises. But nothing prepared me for the visual drama of what came into view around the back of Meister Hall.

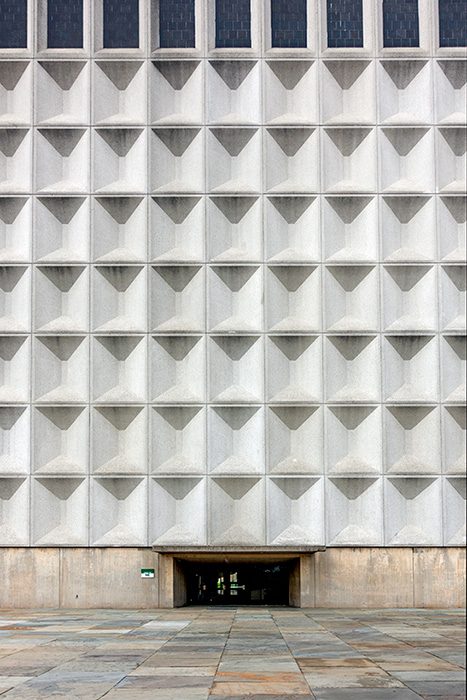

Tech II (Meister Hall), Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

A vast wall of indented concrete panels rose up above a minimalist plaza — windowless — extreme — an uncompromising expression of space and material and nothing else — an opening in the base, the only sign that there is anything habitable behind this eyeless facade. Several interlocking pavilions stood on the plaza with cracked concrete slabs beneath them, like fallen columns.

What can I say. I teared up. Stanford White built his Pantheon echoing Thomas Jefferson on one side of the University Heights quad. Marcel Breuer erected his Parthenon, his Greek temple, on the other side — modernism and classicism melded together as pure sculpture and image.

This, I believe, may be the greatest architectural statement in all New York.

It was the summer and few students were around. There were no other visitors.

Tech II (Meister Hall), Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose

Tech II (Meister Hall), Marcel Breuer — © Brian Rose