Monument Avenue: Grand Boulevard of the Lost Cause

The mysteries of my family history haunt me to this day. At times I have confronted my southern heritage directly, at other times I have run from it. Tomorrow I confront. I am driving to Richmond with my son to photograph the final days of the Confederate statues on Monument Avenue.

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

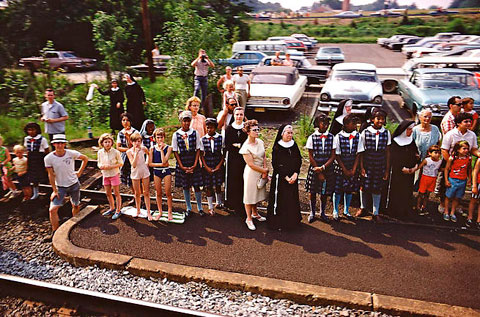

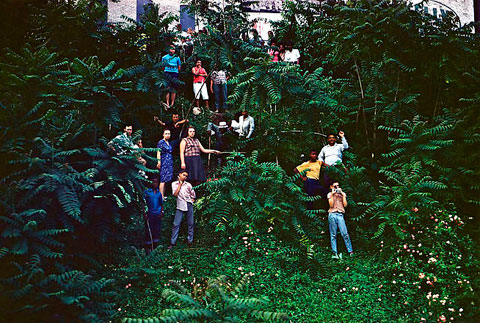

The scene I found in Richmond was extraordinary. Only a week earlier peaceful protesters surrounding the Lee monument were attacked with tear gas, pepper spray and pellets. Now, the protesters had, at least for the moment, occupied the circular park around Lee and appropriated the statue both physically and symbolically, altering its meaning. The atmosphere was jubilant.

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

At one point, a rather fierce-looking motorcycle gang roared up and parked adjacent to the Robert E. Lee statue, and my first thought was “this is trouble.” But they turned out to be the Redrum Motorcycle Club, a Native American club, based in Brooklyn, there to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter protesters.

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

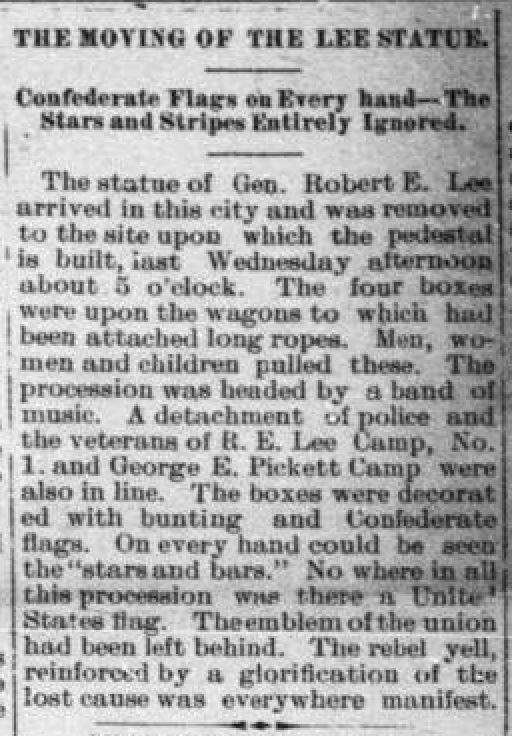

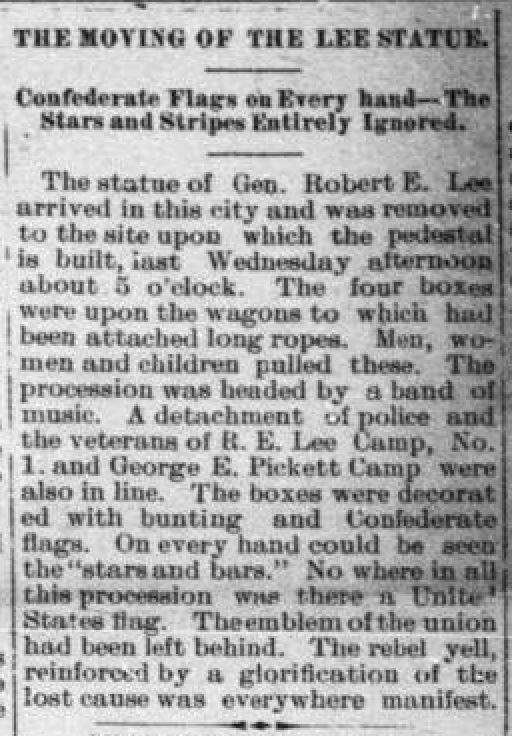

When the Lee statue was unveiled in 1890, thousands applauded the honoring of the South’s greatest hero. Black citizens were not among them. The black-owned Richmond Planet wrote at the time: “This glorification of States Rights Doctrine – the right of secession, and the honoring of men who represented that cause…will ultimately result in handing down to generations unborn a legacy of treason and blood…”

Robert E. Lee statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

A statue of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson stands to the west of Lee on Monument Avenue. Jackson was one of the most venerated of Confederate heroes – the notion that the war might have turned out differently had he not been killed by friendly fire at Chancellorsville has long been a key point of speculation in Lost Cause mythology.

Stonewall Jackson statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Just two weeks since I made my trip to Richmond, the city has removed the Stonewall Jackson statue that stood on Monument Avenue and Arthur Ashe Boulevard. My understanding is that the city intends to remove all of the Confederate Civil War statues as soon as possible. The Robert E. Lee monument remains in dispute because of a lawsuit claiming that the deed for the property requires the city to maintain the monument.

Today, I watched the removal of Jackson live on the internet as riggers swaddled the statue in straps, sawed off the bolts at the base, and lifted the whole thing off the pedestal, setting it gently on the street. Jackson will be placed in storage for the time being.

Stonewall Jackson statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Stonewall Jackson statue, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Last paragraph of a letter to Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney in 2017:

While we do not purport to speak for all of Stonewall’s kin, our sense of justice leads us to believe that removing the Stonewall statue and other monuments should be part of a larger project of actively mending the racial disparities that hundreds of years of white supremacy have wrought. We hope other descendants of Confederate generals will stand with us.

As cities all over the South are realizing now, we are not in need of added context. We are in need of a new context—one in which the statues have been taken down.

Respectfully,

William Jackson Christian

Warren Edmund Christian

Great-great-grandsons of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson

J.E.B. Stuart, Frederick Moynihan, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

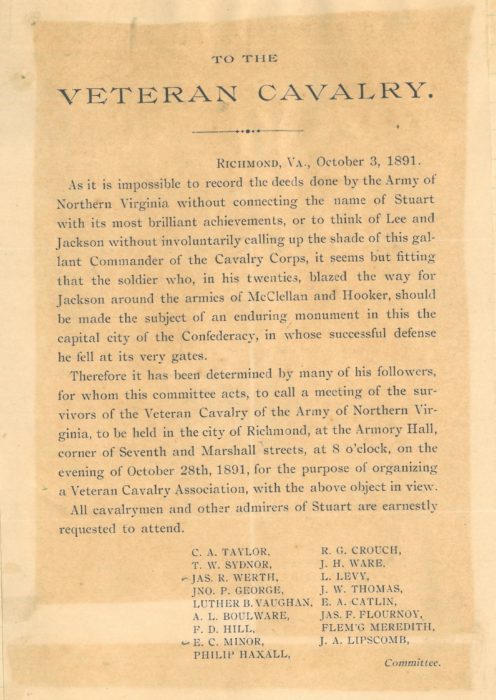

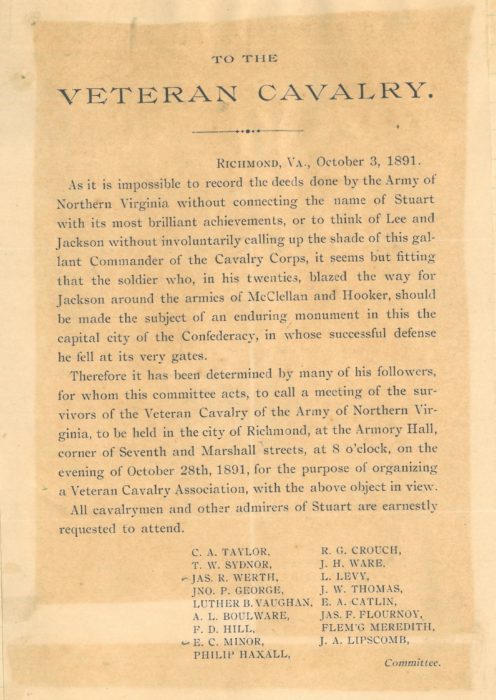

The most animated of the statues along Monument Avenue is that of Confederate general J.E.B. Stuart. It stands in a small traffic circle and its sloped base attracts wheeled acrobatics – at least it does now.

J.E.B. Stuart, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

J.E.B. Stuart, Frederick Moynihan, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

All the statues along Monument Avenue in Richmond are problematic, but none more so than the Jefferson Davis monument. Two nights before I arrived, protesters pulled down the statue of Davis that stood on a pedestal in the center of an elaborate classical pavilion.

Inscriptions on the plaques and stone surfaces extoll the heroism of the Confederate army and navy, and Davis, the president of the Confederacy, himself.

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

A woman walks by the empty pedestal where Jefferson Davis statue once stood. The monument as a whole, however, is more than a tribute to Davis. It is a shrine to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, an ideology based on white supremacy cloaked in words like “freedom” and “rights.” On pillars to the left and right of Davis are tablets inscribed with the poeticized rhetoric of a death cult.

If to die nobly be ever the proudest glory of virtue, this of all men has fortune greatly granted to them, for yearning with deep desire to clothe their country with freedom now at the last they rest full of an ageless fame.

Glory ineffable these around their dear land wrapping, wrapt around themselves the purple mantle of death. Dying they died not at all. But from the grave and its shadows valor invincible lifts them glorified ever on high.

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

With constancy and courage unsurpassed he sustained the heavy burden laid upon him by his people. When their cause was lost, with dignity he met defeat. With fortitude he endured imprisonment and suffering. With entire devotion he kept the faith.

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Matthew Fontaine Maury Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – Brian Rose

While Monument Avenue is infamous for its Confederate generals, there are two other statues. The oddest, perhaps, is the statue for Matthew Fontaine Maury, who was one of the leading oceanographers of the 19th century. He served in the Confederate navy, but his role was limited. Unfortunately, his accomplishments have been eclipsed by his allegiance to the Confederacy.

Matthew Fontaine Maury Monument, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – Brian Rose

His statue was done by the same sculptor, Frederick Sievers, as Stonewall Jackson just walking distance away. It shows Maury seated with a globe and various creatures above him.

When I was there, a swath of purple paint had been applied to his plinth, but I’m guessing the protesters didn’t know quite what to make of this once famous, but now obscure, figure.

Maury was removed from his pedestal yesterday, July 1, 2020.

Arthur Ashe Monument – Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

In 1996 the city erected a statue of Arthur Ashe as a counter-narrative to the glory of the Confederacy. Ashe was a Richmond native, tennis champion, civil rights activist, and advocate for AIDS victims. It was a splendid idea to honor Ashe with a monument.

Arthur Ashe Monument – Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Unfortunately, the statue is an aesthetic disaster, and it’s located at the western end of the avenue where the architectural elegance of The Fan District of Richmond has given way to suburban-style houses. Ashe stands at the top of a cylindrical plinth brandishing a book and a tennis racket while several children reach upward as if pleading for mercy. A powerful figure of Ashe against the sky might have worked, or an approachable Ashe closer to ground level might have worked.

This statue is neither here nor there, and would probably be better not here at all

United Daughters of the Confederacy, Arthur Ashe Boulevard, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Just a few blocks to the south of the intersection of Monument Avenue and Arthur Ashe Boulevard – where the Stonewall Jackson statue stood until recently – the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy sits aloof like a mausoleum of white Georgia marble. Confederate-era cannons flank the entry with its enormous bronze doors.

The night before I arrived, protesters attacked the building with incendiary devices setting off a fire that damaged the library inside and left scorch marks – along with graffiti – on the pristine white facade. The grounds in front of the building were cordoned off with yellow police tape, and several security guards patrolled the pathway leading up to the entrance.

The UDC was the sponsor and defender of many of the Confederate monuments in Richmond and elsewhere. And although their official literature renounces racism and hate groups, their history is highly problematic, to say the least. Through educational outreach and various forms of propaganda, the UDC has done more than any other organization to promote the pernicious myths of the Lost Cause.

Rumors of War, Kehinde Wiley, Arthur Ashe Boulevard, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Rumors of War, Kehinde Wiley, Arthur Ashe Boulevard, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts stands directly next door to the UDC, and in a grassy space in between, a statue by Kehinde Wiley, very much in the spirit of Confederate generals on Monument Avenue, stands on a pedestal, untouched by BLM protesters.

From the VMFA website:

As a direct response to the Confederate statues that line Monument Avenue in Richmond, Wiley conceived the idea for Rumors of War when he visited the city in 2016 for the opening of Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic at VMFA. Rumors of War takes its inspiration from the statue of Confederate Army General James Ewell Brown “J.E.B.” Stuart created by Frederick Moynihan in 1907. As with the original sculpture, the rider strikes a heroic pose while sitting upon a muscular horse. However, in Wiley’s sculpture, the figure is a young African American dressed in urban streetwear. Proudly mounted on its large stone pedestal, the bronze sculpture commemorates African American youth lost to the social and political battles being waged throughout our nation.

Rumors of War, Kehinde Wiley, Arthur Ashe Boulevard, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

J.E.B. Stuart Monument, Frederick Moynihan, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose

J.E.B. Stuart Monument, Frederick Moynihan, Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia – © Brian Rose