In the Shadow of the Highway: Robert Moses’ Expressway and the Battle for Downtown

— © Brian Rose

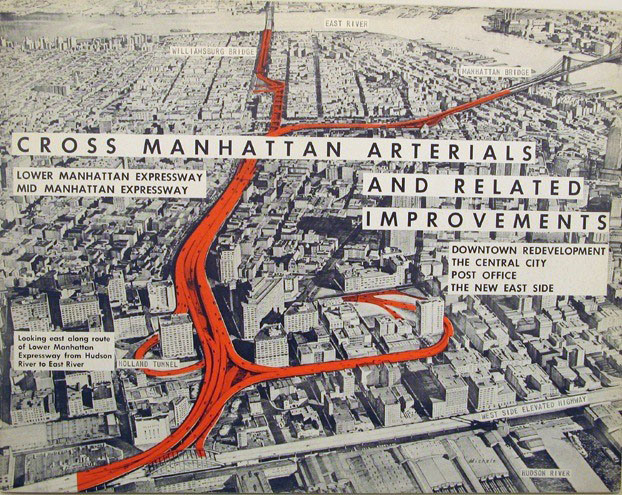

One of my Lower East Side photographs is part of an interesting exhibition about one of Robert Moses’ last projects, a proposed elevated highway that would have connected the Holland Tunnel to the Williamsburg Bridge and an offshoot to the Manhattan Bridge.

Lower Manhattan Expressway brochure

New York Times article about Seward Park site — © Brian Rose

Had Moses not been stopped, Soho would have been largely destroyed, and highways would have torn through parts of the Lower East Side. A piece of that imminent destruction had already taken place when I made my photograph above — a view of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area from the Williamsburg Bridge. Thousands of mostly low income residents were evicted from their tenements to make way for the highway, and nearly 50 years went by before a plan was approved to redevelop the site in an economically balanced way. Although they will have the right to return, it will be too late, unfortunately, for most of the original displaced residents.

Frances Goldin and Brian Rose

There were a number of reasons that Robert Moses, the powerful master planner of New York, was finally stopped. After ramming one infrastructure project after another through neighborhoods all over the city, the tide had turned, and the primacy of automobile-centric planning lost favor. Foremost in opposing Moses and his acolytes were activists like Jane Jacobs, whose book The Death and Life of Great American Cities championed the fine-grained urban fabric of Greenwich Village and similar neighborhoods, and called for their preservation. Other activists took up the cause of low income people, the most at risk from the planners’ bulldozers. Frances Goldin, pictured above, was the most tenacious and eloquent of the Downtown activists.

She and Jacobs represent different perspectives of neighborhood activism, but both were essential in turning things around, and reasserting the right of ordinary citizens to defend their neighborhoods, and, in fact, participate in the planning process. While Goldin is most known for her political actions — her flare for street theater and colorful demonstrations — it was her espousal of neighborhood planning that may be her greatest legacy. Under her leadership, along with the planning expertise of her partner Walter Thabit, the Cooper Square Committee prevented the destruction of a six block strip of the Lower East Side, and in the end, saved or built a thousand units of low income housing. She also led the decades-long fight — after stopping Moses — to redevelop the Seward Park urban renewal site so that it includes a significant percentage of affordable units of housing. A lot of people were involved in these struggles, but she was the glue that held it all together.

Frances Goldin, City Hall Blue Room, 1990 — © Brian Rose

It was my privilege to work with her on the steering committee of the Cooper Square Committee. She and I were very different sorts of players — an array of adjectives come to mind to describe her — brilliant, charismatic, persuasive, indefatigable, optimistic. She was a socialist, Jewish, a quintessentially sharp-tongued New Yorker. I was an artist, soft-spoken Virginian, middle class, protestant background, a Jeffersonian idealist. We clashed at times, but my respect for her deepened over the years, and I think hers for me. One of the things I tell people about Frances is that for all her fierce radicalism, she was ultimately pragmatic and capable of compromise. She got things done. And is still getting things done at the age of 91.

Here’s a recent article in Bedford and Bowery about the history of the Cooper Square Committee.