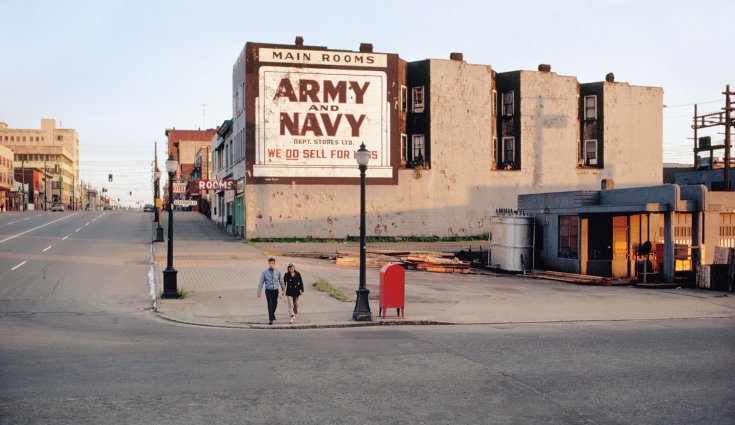

Foot of Main — by Fred Herzog

Foot of Main — by Fred Herzog

A curious thing has happened in the telling of the history of color photography. In recent years, it was discovered that two photographers, Fred Herzog of Vancouver and Saul Leiter of New York, had worked in color long before the familiar names associated with the development of the medium. And their color work was not just a casual sideline to black and white. Both produced extensive bodies of work made over years of time. While I prefer Herzog’s clear topographic style to Leiter’s aqueous street photos, they both did terrific stuff. Why are we only hearing about them now?

Two photographs by Saul Leiter

Two photographs by Saul Leiter

When I decided to pursue color in the mid-70s, there was no Fred Herzog or Saul Leiter to be found. I was primarily aware of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston–and Joel Meyerowitz who I studied with at Cooper Union. As it turns out, Herzog and Leiter had been shooting color slides for decades, showing them to friends and colleagues, but outside of their immediate circles, they were almost unknown. Herzog was documenting Vancouver, British Columbia, a dynamic, growing city, but until relatively recent times, a provincial town far removed from the East Coast art centers. Leiter was known more for his fashion photography, and as he said, to explain his relatively low profile: “In order to build a career and to be successful, one has to be determined. One has to be ambitious. I much prefer to drink coffee, listen to music and to paint when I feel like it.”

There are many reasons why it took so long for color to arrive to the museums and galleries, but the key thing to understand is that before the 1970s, color printing was problematic. Chromagenic prints (C-prints) were invented by Kodak and brought to the market in 1942. Well into the 70s this material was mostly associated with family snapshots, and as anyone who has looked at old color prints knows, the color faded and the paper yellowed. It was possible to have enlargements made–you could have your local photo finisher make an 8×10 print. But you had no control over the final outcome. For these reasons, early C-prints were not suitable for fine art purposes.

Magazines like National Geographic and Life began to use color in 60s, but they worked directly from slides or large format transparency material. which were made into separations for offset printing. That was the norm for magazines right into the 1980s. When I began photographing architecture around 1982, all my clients still wanted 4×5 transparencies, luminous sheets of film handled like irreplaceable jewels. The impetus for color printing–the kind that went on the walls of galleries came from elsewhere.

To a degree, fine art color printing was born out of the advertising industry. Photographers were shooting color transparencies and the ad agencies had dye transfer prints made, an additive process that involved making color separations and sandwiching them together–much too complicated to get into here–but a method of color printing that provided a great deal of control over the final result, often an intentionally unnatural result for ad purposes. It was a time consuming and expensive process, but worth it to the ad agencies.

At some point, photographers realized that dye transfers were a stable archival material that could be used to make beautiful fine art prints. Joel Meyerowitz, who worked in advertising, made dyes of his early 35mm street photography, and William Eggleston’s prints shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976 were dye transfers. Helen Levitt’s color prints were made by Tartaro Color, the leading dye lab in the city. Most of us could not afford to make dye transfers, though I remember one of my fellow students at Cooper Union, whose father worked in the industry, had his slides printed as dye transfers. I was jealous. Eventually, with improvements to C-printing and the advent of ink jet printers, the medium of color photography rapidly expanded in the 1980s.

Things had already begun to improve when I first started color printing in the darkroom at Cooper Union in 1977. I made 11×14 prints in drums, pouring the chemicals in and out by hand, often ending up with green chemical streaks on the paper, which meant starting over again. It was laborious work, but I managed to make about 25 prints for an exhibition in the hallway of the photography department. Since I was shooting 35mm slides–a positive film, and printing on reversal material–I had to have internegatives made from the slides. There were only a few labs in New York City that specialized in that kind of thing, but at least here it was possible. The prints I made back then look pretty bad today. In the early 80s I printed at a rental lab called My Own Color Lab, which gave individuals access to large scale processors used by commercial labs. For a number of years My Own was a Mecca for color photographers and free lance printers, and there I came into contact with people like Nan Goldin, Andreas Gursky, and Phillip Lorca DiCorcia.

Main Barber — by Fred Herzog

Main Barber — by Fred Herzog

But if you were Fred Herzog in Vancouver shooting Kodachrome in the 50s, 60s, and 70s there was really no way to make decent exhibition prints. You loaded the slides into a Kodak carrousel tray and projected them just like your neighbors showing their latest vacation snaps. The amazing thing is that Herzog kept at it for decades, all the while eschewing the pictorial cliches of the day, taking a hard look at a beautifully gritty place, a Canadian city both familiar and foreign, full of advertising signs, fin-tailed automobiles, and working class men and women. It’s a remarkable achievement, all done outside of the art world bubble, full of a freshness and sense of discovery so often lacking in the arch and self-conscious product presently displayed in our finest salons.

So, the narrative has changed. Leiter and Herzog were first–but their photographs, 35mm Kodachromes, were mostly unseen–until after the big wave of color photography had crashed ashore establishing a pantheon of art world stars. They eventually received the attention they deserved, but very late. Saul Leiter died last year at the age of 90, and Fred Herzog is now 83.