Lower Manhattan by Corinne Vionnet

Photographic plagiarism is an almost meaningless concept. I don’t mean the stealing of copyrighted images, which is generally a well-defined legal matter, but the idea that particular images of places and things are proprietary, that repeating the same view, or imitating another photographer’s compositional approach, constitutes an infringement of someone’s unique vision. It is possible to point disapprovingly at photographers who deliberately copy the work of others. You can call them unoriginal, even unethical. But it is a slippery slope to go down because the reality is that the visual world is fair game.

Corinne Vionnet’s images of popular tourist sites around the world demonstrates this well. She combines hundreds of photos available from Flickr and other photo sharing services taken from similar perspectives creating ghostly mimetics–pictures of pictures–expressing collective visual iconography.

Vionnet:

The images made by tourists are picture imitations. They demonstrate the desire to produce a photograph of an image that already exists, one like those we have already seen. It is in fact a style of manipulating the viewer. Why do we always take the same picture, if not to interact with what already exists? The photograph proves our presence. And to be true, the picture will be perfectly consistent with the pictures in our collective memory.

The Brandenburg Gate by Corinne Vionnet

I use the two image above because they include icons that have figured prominently in my own work. Although I strive for images that go beyond visual cliches, I have never entirely avoided the obvious or the commonplace. The urban landscape we live in–even the natural landscape–is to a great extent prepackaged, designed, and pre-consumed. I consciously work with and against these structural constants, both physical and those imprinted on our brains. The pictures below could easily work into Corinne Vionnet’s Brandenburg Gate compilation.

The Brandenburg Gate, 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The Brandenburg Gate, 1989 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The Brandenburg Gate (4×5 film) –© Brian Rose

All three of my Brandenburg Gate pictures are locked into the axial and symmetrical nature of the space and architecture, but they are all on some level meta-images, images about images, a step removed from representation of the icon itself.

As much as I feel that I own the subject of the Berlin Wall, and to a much lesser extent Berlin itself, there have been lots of other photographers who have covered the same terrain, sometimes coming up with startlingly similar images. I have known and admired John Gossage’s work since I was a student. His book The Pond has recently been re-released. I did not know, however, until a short time ago that he also photographed the Berlin Wall back in the 80s around the same time I was there. Here are two of our photographs taken from similar vantage points:

The Berlin Wall by John Gossage

The Berlin Wall (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

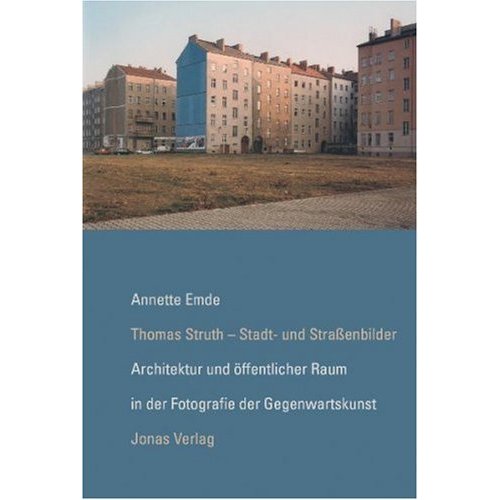

Another photographer I greatly admire is Thomas Struth, who has photographed streetscapes and architectural subjects all over the world including Berlin. Just after the Wall came down he and I, unknowingly, both photographed along Bernauerstrasse where a wide swath of former no man’s land sliced through rows of buildings in the neighborhood Prenzlauerberg. Here are two pictures:

Photograph by Thomas Struth

Bernauerstrasse (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The world is awash in images. Legions of photographers, professional and amateur, have fanned out across the globe to document seemingly every scrap of land and every crumbling ruin no matter how banal. For me, it is occasionally deflating, thinking about this glut of imagery. But I have been doing this for a long time, doggedly following my nose where it leads, ignoring the trends and the crowds. Sometime, when I set up my view camera, people point their cameras over my shoulder, or even stand right in front of me and take a picture of what they think I am photographing.

What to make of all these similar images of the same subjects? For one thing, they are rarely identical. A millimeter this way or that can make all the difference. The transient quality of light and atmosphere. The passing stray cat, the discarded soda can, the random interplay of people moving through the scene. All these variables give the image its uniqueness. But what’s equally important, I think, is not the individual photograph, but the gradual accretion of images made over an extended period of time by a particular photographer.

I think it’s inevitable that photographer’s paths will cross and images occasionally overlap. You can’t copyright a view, and there are a lot of 1/125ths of a second to go around. Imitators will be seen for what they are. But don’t try to steal one of my images of the Brandenburg Gate. If you don’t want to pay for the rights, you can always go to Berlin, find where I stood, and get your own Brandenburg Gate.