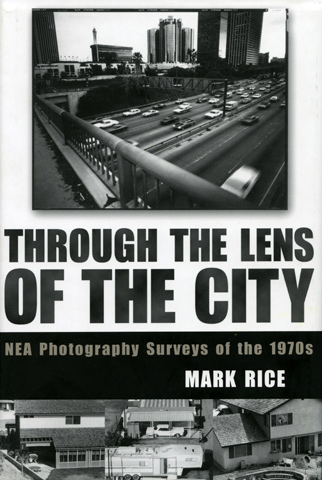

Book cover with images by Bill Owens and Joe Deal

Final comments on Mark’s Rice’s Lens of the City, NEA Photography Survey of the 70s. I was a participant in one of these surveys in 1981. Scroll down for other posts.

Much of the book is spent exploring the art/documentary dichotomy, which was highly controversial during the years that the NEA funded survey project between 1976 and 1981. Many of the commissioned photographers operated in a traditional documentary manner–a sort of long form of photo journalism. But others, the ones we are most likely to know about today, were working under different precepts. These photographers, Robert Adams, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, among others, created images that were factual but neutral, allusive rather than didactic–and it was understood that photographic truth was by its nature contingent.

Many critics and viewers were unsatisfied with photography that did not “tell,” but rather suggested, or simply raised an eyebrow. It would seem that the result of all the projects funded by the NEA was an unfocused, discursive view of the American urban scene. Certainly, the project I was involved with–photographing the Lower Manhattan in 1981–was a curious mixed bag of photographic styles and approaches. Ed Fausty and I, working together and later alone, were the youngest of our group, and we were working in color with a view camera while the rest were shooting in black and white with small cameras. I don’t remember the other photographers’ work except for Larry Fink who photographed the hurly-burly atmosphere on the floor of the stock exchange.

The NEA projects may have been uneven in quality, but individual photographers often did exemplary, even groundbreaking, work. Several of the projects funded the work of single photographers with noteworthy results. Joel Meyerowitz’s St. Louis and the Arch and Lee Friedlander’s Factory Valleys were among the finest explorations of the urban landscape of their era. Friedlander’s project extended beyond place by incorporating images of people and the machines they operated. These are some of his strongest photographs–formally arresting, as always, but simultaneously expressive of the human condition.

In the end, the NEA survey grants were killed not so much by disagreement about what constituted art vs. documentary photography, but by the ascendancy of conservative politics. It did not matter that the survey grants were administered by local institutions and communities, nor did it matter that the grants were required to find matching funding from private sources. The survey grants ended with Ronald Reagan’s election, and in a few years, the individual artists’ grants would also be eliminated. We have had a neutered and ineffectual National Endowment for the Arts ever since.

Government funding of the arts will always be problematic, but when art is left primarily to the galleries whose interests tend toward protecting relatively small stables of brand names, the result is brutally Darwinian. Meanwhile, the schools keep churning out MFA grads, and a cottage industry built on webzines, blogs, contests and portfolio reviews picks up the slack, sometimes receiving funding from the NEA and private benefactors. But where is the support for individual artists? When I think of the burst of work done during the few years of the NEA survey grants–made for a minuscule fraction of the NEA’s budget of around $150 million in 1980–well, it’s obvious that our priorities are a tad skewed.

I don’t recall exactly how much money I got to do my photographs of Lower Manhattan. Maybe $2,500. At the time I was 27 years old, and it seemed like a fortune.