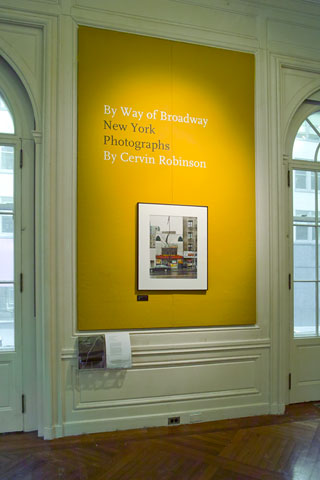

A few weeks ago I went to Cervin Robinson’s opening at the Urban Center Gallery. It was a crowded affair, and not a good moment to look at the photographs. So, yesterday I returned to the exhibit, By Way of Broadway, and spent some time with the pictures.

The gallery consists of two large rooms of the former Villard Houses, which now are home to the Municipal Arts Society and the Urban Center bookstore. The Palace Hotel uses part of the original buildings as well, and its bland tower looms over the entry courtyard seen above. How that happened is a story in itself.

Cervin Robinson at the Urban Center Gallery — © Brian Rose

Despite the use of the rooms as a gallery, their historic appearance has been preserved. But that means that any exhibition mounted has to contend with wainscotting and other architectural details. It’s beautiful, but not always the most flexible space, much like the old ICP galleries, which were housed in a historic mansion on East 94th Street.

Urban Center Gallery — © Brian Rose

On one wall of the gallery (pictured above), a fireplace has been covered, and a large mirror stands above it. Casement doors connect the gallery to the main lobby. It’s a gracious and dignified space, and works pretty well for Cervin Robinson’s equally well-mannered photographs.

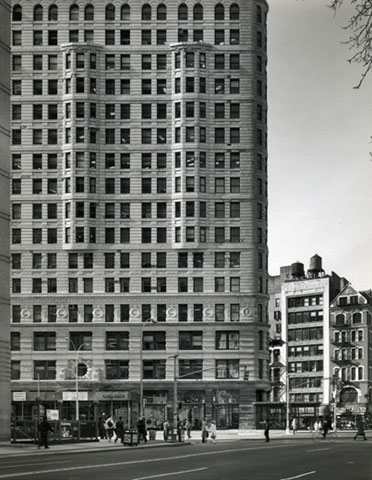

Cervin Robinson, the Flatiron Building

Robinson is one of a handful of photographers who defined what is understood today as architectural photography. He is in the company of the late Ezra Stoller, and Julius Shulman, who is still with us in his nineties. Dutch photographer Jan Versnel–not well known in the United States–was another of this select club. Together, they not only helped establish the profession of architectural photography, they also made the images that form our collective awareness and recognition of important works of architecture.

TWA Terminal — photo by Ezra Stoller

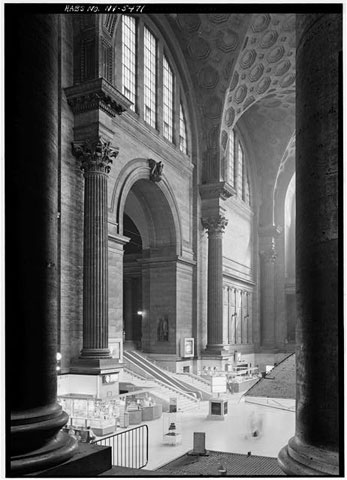

When we think of Saarinen’s TWA terminal, we see it through the pictures that Stoller made of that swooping structure. When we think of the Case Study houses of Southern California we see them through the photographs of Julius Shulman. And when we think of the innovations of Louis Sullivan, or remember the much mourned Pennsylvania Station by McKim Mead and White , we do so with the help of images made by Cervin Robinson.

Pennsylvania Station — photo by Cervin Robinson

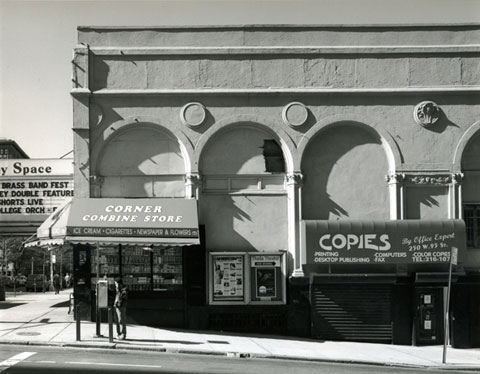

The show at the Urban Center, however, is not about Robinson’s commissioned work or extensive book projects. This series of images focuses on Broadway, Manhattan’s slightly meandering street that runs from tip to tip of the island. It’s one of America’s principle thoroughfares–Wall Street lies perpendicular to it, Times Square is formed by its vector across Seventh Avenue, and it brushes the corner of Central Park at Columbus Circle. Further uptown it slices past Lincoln Center, bisects the campus of Columbia University, crosses 125th Street in Harlem, eventually leaving Manhattan and continuing up through the Bronx and further upstate as route 9.

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Robinson’s photography can be difficult to write about because there is so little artifice in it. One of the things architectural photographers learn is that they have an obligation to the building they are documenting–that their own style or signature as a photographer must take a backseat to allowing the architectural object to come through. Robinson brings this same self-effacing approach to his personal work in the streets of New York.

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Here the object is more diverse, multifaceted, but Robinson finds in the jumble of the city points of attention, organizing elements in an otherwise chaotic scene, and always, the beauty of structures both grand and humble. In the years he has been photographing Broadway, many of those structures have disappeared, preserved only by his view camera. And Robinson returns dignity to lost art deco gems, obscured by signs, robbed of their original functions.

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Robinson does this without a note of lachrymosity, though we may weep for the things he reveals. Above all, however, Robinson celebrates the richness of the architectural heritage of the city–and although he remains even handed in his attention to the cityscape new and old, his eye lingers on the crafted masonry facades of pre-war New York. But despite Robinson’s objective acuity, it is his street–he lives on Broadway–and in the end By Way of Broadway is a personal project, the linear path of a life devoted to describing the city, the nature of place, and the ennobling power of architecture.

The entire exhibition can be viewed here.