-

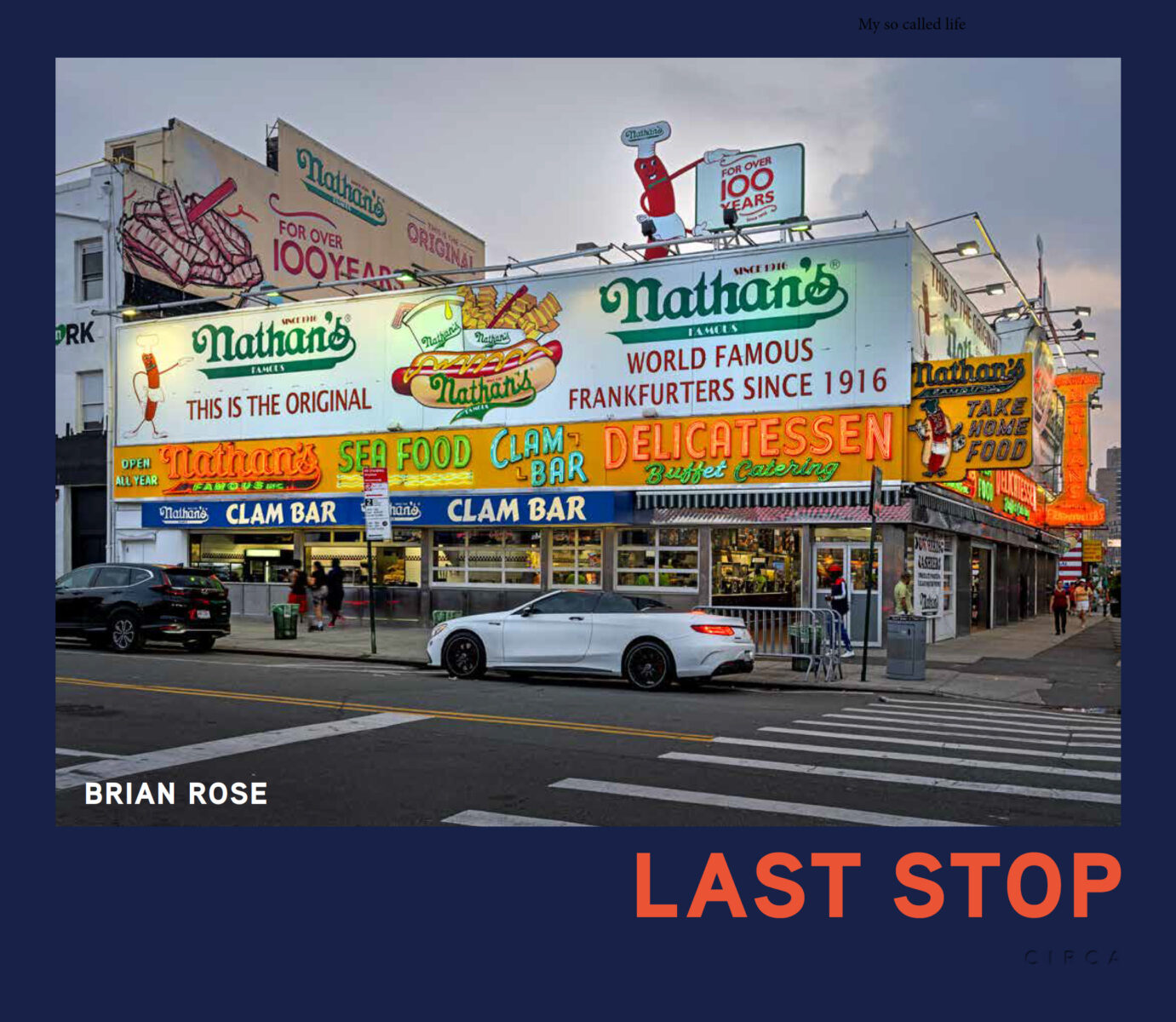

Last Stop – New York City

Over the course of a year, I have photographed the neighborhoods at the ends of all of the subway lines in New York City. There are multiple reasons for engaging in this project, but the strongest for me is a desire to portray New York as a highly diverse, multi-centered metropolis, one that has expanded and grown far beyond Manhattan and some of the well-known neighborhoods of Brooklyn. Manhattan, while still central to the story, has become more homogenous with little manufacturing and few of the distinct market districts like the historic Fulton Fish Market and Meatpacking District that once defined the fabric of the city. Those areas are now entertainment and shopping destinations. Like most of the major cities of the world, New York City has become a tourist mecca and a staging platform for international brands.

Bedford Park, The Bronx Many New York old-timers cling to the past and insist that “back then” was the authentic city, suggesting that the present is a kind of faux New York, a shadow of its grittier, more vital, self. I understand where that perspective comes from, but it is belied by a population that has grown tremendously since the ‘70s and ‘80s, and by the spatial atomization of the city that has created a galaxy of new economic centers and ethnic enclaves. I discovered that new city as I rode the subway system to its far-flung reaches.

I did the entire project on foot and by train, visiting 44 locations, some more than once. I researched each neighborhood before setting out, often “walking” the streets on Google street view to get a feel for the lay of the land. But no amount of virtual travel compares with actual experience, and each neighborhood I explored offered surprises and moments of revelation. My perambulations took me from the glassy tourist havens of Hudson Yards to some of the poorest areas of East New York.

East New York, Brooklyn Having spent a major part of my career photographing New York through often challenging times – the dichotomy of destruction and creativity of 1980, the mortal wounding of 9/11, and the suspended animation of the Covid-19 pandemic – I felt that I was uniquely equipped to document New York at this moment of political uncertainty under the increased strain of new arrivals, many of whom are refugees from around the world. For a new generation of New Yorkers, the trains roll on ceaselessly, and despite the title, “Last Stop” is not so much about endings as it is about reinvention.

You can find Last Stop in book stores and online on Amazon:

https://a.co/d/0X7dxP9 -

Washington DC

Georgia Avenue, NW, Washington, DC – © Brian Rose We took the Metro up Georgia Avenue at least two miles north of the White House in a busy, racially mixed neighborhood. I photographed the now iconic Banksy-inspired image of a protester throwing a sub sandwich at, in this case, Trump’s ghoulish henchman, Stephen Miller. Just a couple of weeks ago, a protester threw a Subway sandwich at a National Guardsman at 17th and U Street. He was chased and retreated to his apartment. When he offered to turn himself him, homeland security, instead, arrested him with a large contingent of heavily armed officers. Afterwards, they released a slick video of the arrest making it appear that they were apprehending a dangerous criminal. Homeland security charged him with felony assault, but the court knocked it down to a misdemeanor.

17th and U – © Brian Rose Down at 17th and U I found the original Subway store where the hoagie hurling incident occurred, but there was nothing of significance to see. However, just down the street in an alley I came across another poster of the sandwich thrower, posed like an NFL quarterback attempting an end zone toss. Beneath the image was the slogan “Free DC.”

Alley off of U Street – © Brian Rose For the fever swamp right wingers, this graffiti-strewn alley could certainly serve as evidence that Washington is a crime-ridden hellscape, except that there was nothing going on and the whole neighborhood felt pretty normal in a somewhat urban gritty kind of way.

EPA building, 12th Street, NW – © Brian Rose Walk by the government buildings along Constitution Avenue, we passed by the side entrance of the partly abandoned EPA building. The doors were locked, and a poster, obviously a forgotten relic of days gone by, touted the use of green energy. “This Building Runs on (windmill) Power.

As we walked up 15th Street we encountered groups of young men in blue suits and brown shoes, apparently the uniform of the new right wing conservative cadre now running things in DC. Among them, coming out of a doorway, was Nigel Farage, the British member of parliament and head of UKIP, a reactionary British political party.

Andrew Jackson statue, Lafayette Square, the White House – © Brian Rose One can only approach the White House by walking through Lafayette Square as the grounds have become gradually more fenced off and fortified. The square is named for the French hero of the Revolutionary War, but the centerpiece of the park is the statue of Andrew Jackson, a highly complex figure in American history. Jackson was a war hero, a populist, and the instigator of “the trail of tears,” a genocidal expulsion of Indian tribes located in the southeast states.

The White House – © Brian Rose

The Peace Tent – © Brian Rose Wikipedia:

The White House Peace Vigil was an ongoing protest calling for nuclear disarmament world peace. Erected in 1981 it was possibly the longest continuous protest action in American history. Two days after I photographed the tent, Trump heard about its existence and ordered its removal. I joked with my son that it was my fault for taking the photograph.

Wikipedia:

- “On September 5, 2025, President Donald Trump, claiming to have been made aware of the vigil’s existence for the first time, ordered his staff to remove it that day. On September 7 around 6:30 a.m., federal officers forcibly removed a tent-like structure used by the vigil, though the vigil itself remained staffed and its physical presence continued uninterrupted throughout the incident. The vigil was fully reassembled shortly thereafter.”

Lafayette Square – © Brian Rose Before leaving the park, I took a picture of a decorative urn on a stone pedestal. It’s not a well-known monument, and in fact, not that much is known of its origin. The sun was setting, and Washington, rather than feeling like a city under siege, felt somnolent, only half alive. One senses that the center of power is empty at the core. While there is great danger posed by the reckless greed, vindictiveness, and mental illness of the sitting president, there is at the heart of the matter an empty suit, a rotting corpse, nothingness.

- “On September 5, 2025, President Donald Trump, claiming to have been made aware of the vigil’s existence for the first time, ordered his staff to remove it that day. On September 7 around 6:30 a.m., federal officers forcibly removed a tent-like structure used by the vigil, though the vigil itself remained staffed and its physical presence continued uninterrupted throughout the incident. The vigil was fully reassembled shortly thereafter.”

-

Washington, DC

Labor Department – © Brian Rose Although we planned the trip down from New York to coincide with the Epstein press conference at the Capitol, my goal was to get a photograph of one of the giant murals of Donald Trump that festooned two government buildings along the Mall. I’d seen photographs, but was frustrated that none of them captured the full authoritarian bombast I assumed was present when there in person. In that regard, the scene in front of the Labor Department building at the corner of Constitution Avenue and Pennsylvania Avenue did not disappoint.

National Gallery of Art, Blue Rooster – © Brian Rose From there, we got lunch in the National Gallery cafeteria, and took the elevator to the roof terrace of I.M. Pei’s East Wing. The view of the Labor Department mural was a bit distant, but I got a nice shot of the blue rooster, or officially “Hahn/Cock” by Katherina Fritsch. It originally stood on the fourth plinth, the empty pedestal, in Trafalgar Square, London.

The rooster has roosted on the roof of the National Gallery since 2017 when the art critic Blake Gopnik suggested that Fritch’s sculpture had become a symbol of DC’s resistance to the newly installed president.Artnet:

As it looks out over the city, Fritsch’s creature now seems on guard. I imagine it coming to life to sound the alarm if our nation and values look set to collapse. For Washingtonians, at least, a blue that might once have evoked summer evenings or the art of Yves Klein now stands for a full-fledged state of depression.

-

Washington, D.C.

Washington, DC – Epstein press conference – © Brian Rose I made a quick trip to DC to see for myself what was going on. Trump had called up the National Guard to put down a fictitious wave of crime gripping the city. There’s crime in Washington, for sure, but violent crime is mostly confined to the poorest neighborhoods, well away from the government buildings and monuments. Arriving by train with my son Brendan, we found a city in a strange liminal state. There were a few bored National Guard troops walking around Union Station, but there was little evidence elsewhere of a crackdown. But ICE and other factions of Trump’s goon squad were active in the city, though we did not see them. Tourists had gotten the message, and the Mall was largely deserted. Downtown, the stores and restaurants were open, but the vibe subdued.

Epstein press conference – © Brian Rose Our train arrived somewhat late because we had to take on extra passengers from a stranded train in New Jersey. My immediate goal was to take pictures of a press conference held by several House representatives and a number of victims of Jeffrey Epstein, the convicted pedophile, and close friend of Trump, who supposedly committed suicide in a Federal detention center in New York. The unreleased Epstein files hang like a Sword of Damocles over Trump and any number of other prominent political and business leaders who were associated with Epstein.

Between the Capitol and the Library of Congress – © Brian Rose As we approached the presser taking place adjacent to the House steps, a squadron of fighter jets flew low overhead – possibly an intentional disruption. The official explanation, given later, was that it was meant to honor a Polish airman who had recently died in a crash. In the large meadow between the Capitol and the Library of Congress a banner read “You are all Cowards.”

The Capitol, Washington, DC – © Brian Rose Walking from the press conference, I photographed the west front of the Capitol, majestic and in pristine condition. Just six years ago, thousands of Trump supporters besieged the building, smashing in doors, scaling walls, and assaulting the Capitol police. When I was still a student, just before moving to New York, I lived for a time in Washington and worked as bike messenger. I went in and out of the Capitol many times with packages and envelopes intended for elected leaders and their staffs. Security was relatively light in those days, and I rarely needed to show ID as I was waved in past the tourists waiting in line. It was always a thrill to walk into the rotunda with the dome soaring high above. Whatever the failings of the United States – and there are many – the desecration of this building was a direct attack on the ideals that transcend these shortcomings.

-

New York/The Real Estate Show

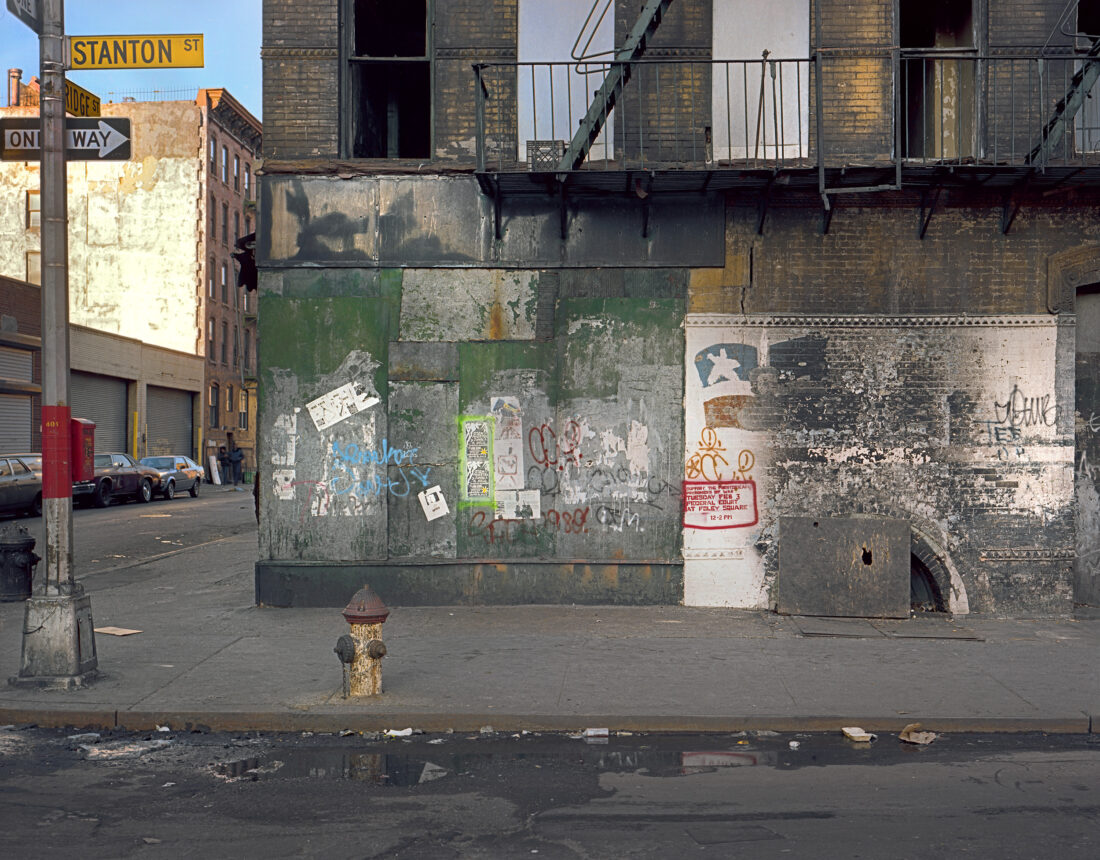

Stanton Street, NYC, 1980 – © Brian Rose / Edward Fausty ⠀ ⠀ ⠀ The photographs we made in 1980 sometimes contain hidden secrets that we may or may not have been aware of at the moment of taking the picture. In this case, not quite readable at internet resolution, is a torn sign pasted to the front of the abandoned building at Stanton and Ridge that says “The Real Estate Show.” ⠀ ⠀ ⠀

In 1980, a group of artists calling themselves Colab took over a small empty building on Delancey Street and displayed art work addressing city plans for developing the largely empty site. They sought to connect the interests of low income people to their own as artists. Whether they succeeded is open for debate, but the initiative led to the formation of ABC No Rio, which still thrives as a neighborhood arts organization. ⠀ ⠀ ⠀

“In 1980, a group of artist-activists entered an abandoned building on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and staged an exhibition on gentrification and property ownership. The occupation lasted little more than a day before the police shut it down. During that brief time, Joseph Beuys came, looked, and left, and so did a handful of others—neighbors, city officials, reporters—and this bold flash of an exhibition is today remembered as one of the most significant art events of its era.” – Alan W. Moore⠀ ⠀ ⠀

There is an unbelievable amount of information on the web about this extremely short-lived exhibition. but you can start here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Real_Estate_Show

-

Diane Arbus – New York

Diane Arbus is one of the most important 20th century photographers. Whether you find her images difficult to digest, or painfully out of sync with present-day mores, her photographs of outcasts and misfits remain powerful, and once seen, never unseen. Even her images of ordinary individuals feel slightly discomfiting, too revealing. Ensnared by Arbus’s camera, we are all uniquely strange beings, though often quite beautiful in our individuality.If you want to see Arbus’s work – virtually all of it – go see Constellation at the Park Avenue Armory. It is a spectacular installation. Unfortunately, for me, the installation competes too much with the images, which in many cases, are difficult to see because they are hung too low or too high, or inadequately lit. The back wall of the already vast exhibition is a floor-to-ceiling mirror that appears to double the space. I started to walk into the reflection but stopped short when I came face-to-face with myself surrounded by Arbus’s images floating in space. The funhouse effect suggests a connection, perhaps, to the many carnival and circus subjects that Arbus photographed.

The intro text lays out the rationale for the non-hierarchical gridded structure of the exhibition, and a side text explains how Neil Selkirk, who made the prints after Arbus’s death by suicide, attempted to reproduce her original intentions. The quality of the prints is extraordinarily uneven, and in many cases murky and blocked up. Moodiness is sometimes just muddiness. I do not believe that photographers’ prints are sacred, although originals will always have a primary importance. Photographers can bring great skill to the darkroom – or computer – but sometimes, the task is best left to others. A more illuminating retrospective of Diane Arbus’s work might include newly made prints by someone unconnected to her. I don’t expect that to happen.If you’re thinking of going, keep in mind that the entrance fee is $25. Despite my reservations about the installation, it is well worth seeing and thinking about.

-

The Problem with Jacob Riis

Article first published in Frames, the photography magazine

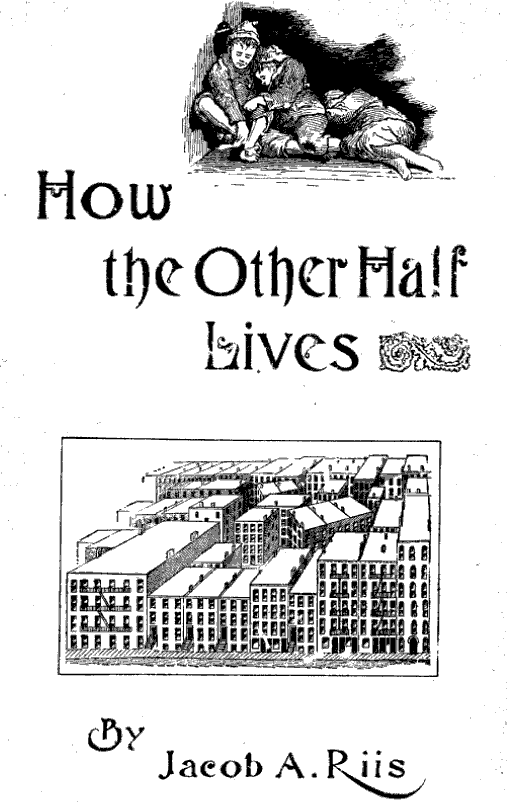

https://readframes.com/food-for-thought-the-problem-with-jacob-riis-by-brian-rose/Jacob Riis is widely acknowledged as a social activist and a groundbreaking documentary photographer who, in the late 19th century, exposed the squalor of the slums on the Lower East Side of New York. In his impassioned advocacy for better housing design and educational opportunities for the immigrant poor, he became one of the most famous men in America. What is less recognized is that he viewed his subjects through a profoundly racist lens. It’s time to reexamine the legacy of, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, New York’s “most useful citizen.”

For a number of years. I’ve led a class at the International Center of Photography on photographing the Lower East Side of New York. The students take pictures of the neighborhood, cognizant of the rich history of the neighborhood as portal to America, and we assemble a book that is presented to the ICP library. In many ways, the history of photographing the Lower East Side closely follows the history of photography in general. Many of the most important innovators of the medium lived or worked in the neighborhood. The list includes Lewis Hine, Paul Strand, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Weegee, Helen Levitt, Walter Rosenblum, and recently, Nan Goldin. The names go on and on, but the story always starts with Jacob Riis, the Danish immigrant, whose beat as a police reporter covered the Lower East Side.

His photographs are blunt and unflinching, almost anonymous in style, attributes that, in the 1960s and 70s when his work was rediscovered by a new generation of scholars, helped usher him into the canon of art photography. John Szarkowski, photo curator at the Museum of Modern Art, featured his work in “Looking at Photographs,” published in 1973, and in an essay in Artforum in 1981, Colin Westerbeck writes: “The paradox of Riis’ posthumous reputation is that photographers now make art by doing what he did in order not to make art.”

Jacob Riis Riis made photographs primarily to accompany his newspaper writing and to provide illustrations for his lantern slide lectures, in which he shocked his middle-class audiences with images of people living amidst filth and crime, and what he described as moral depravity brought on by poverty and cramped tenement housing. Riis focused especially on the dark and airless rooms of typical Lower East Side dwellings, and promoted the development of more humane “model tenements.” He was a religious zealot – or, to use his own word, a crank – on a crusade to right society’s wrongs. And he made a difference. His hectoring criticism of tenement landlords led to better housing design, and his concern for the education of children led to the creation of settlement houses that provided a wide array of social services. At the same time, however, he gave scant attention to the labor movement of the late 19th century and preferred Christian charity to a progressive reordering of society.

His crowning achievement was the book “How the Other Half Lives,” published in 1890, which was among the first publications in history to combine text and photographs. It was a best seller and made its author famous, if not rich. It was also a luridly written extended essay of “scientific” observations about the myriad ethnicities occupying Lower Manhattan. “One may find for the asking an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony. Even the Arab, who peddles “holy earth” from the Battery as a direct importation from Jerusalem, has his exclusive preserves at the lower end of Washington Street. The one thing you shall vainly ask for in the chief city of America is a distinctively American community. There is none; certainly not among the tenements.”

Each group’s appearances and cultural attributes are described in detail. “With all his conspicuous faults, the swarthy Italian immigrant has his redeeming traits. He is as honest as he is hot-headed.” “…I state it in advance as my opinion, based on the steady observation of years, that all attempts to make an effective Christian of John Chinaman will remain abortive in this generation; of the next I have, if anything, less hope.“ Of Jews, Riis writes: “Money is their God. Life itself is of little value compared with even the leanest bank account.” And Blacks: “The poorest negro housekeeper’s room in New York is bright with gaily-colored prints of his beloved “Abe Linkum,” General Grant, President Garfield, Mrs. Cleveland, and other national celebrities, and cheery with flowers and singing birds.”

Riis was, it should be pointed out, sympathetic to the fate of Blacks after the Civil War, and states succinctly: “If, when the account is made up between the races, it shall be claimed that he falls short of the result to be expected from twenty-five years of freedom, it may be well to turn to the other side of the ledger and see how much of the blame is borne by the prejudice and greed that have kept him from rising under a burden of responsibility to which he could hardly be equal.” Nevertheless, “How the Other Half Lives” is a tough slog, page after page of the vilest stereotypes and judgments on human character.

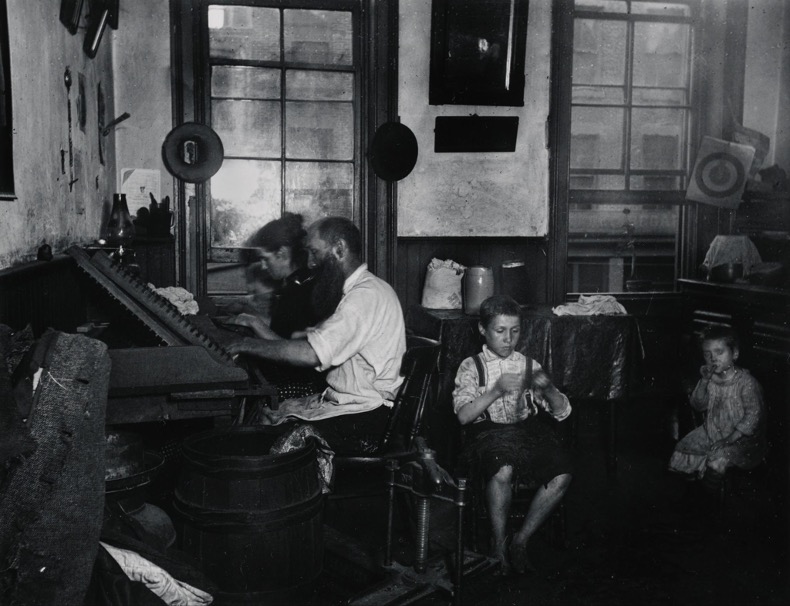

Jacob Riis This brings us to his photographs, the principal reason for our continued interest in Riis. The great irony is that Riis did not consider himself a photographer, nor did he think his images were of particular aesthetic value. Some of his photographs were even made by assistants or hired guns. They served a purpose, nothing more. Lantern slides for his lectures were the primary use, as halftone screening for printing in magazines and newspapers did not become practical until near the end of his life. Riis did not make photographic prints for display, and certainly, no gallery or museum would have considered his work appropriate for their walls. When he donated his archive to the Library of Congress at the end of his life, it included his books and essays but, significantly, no photographs.

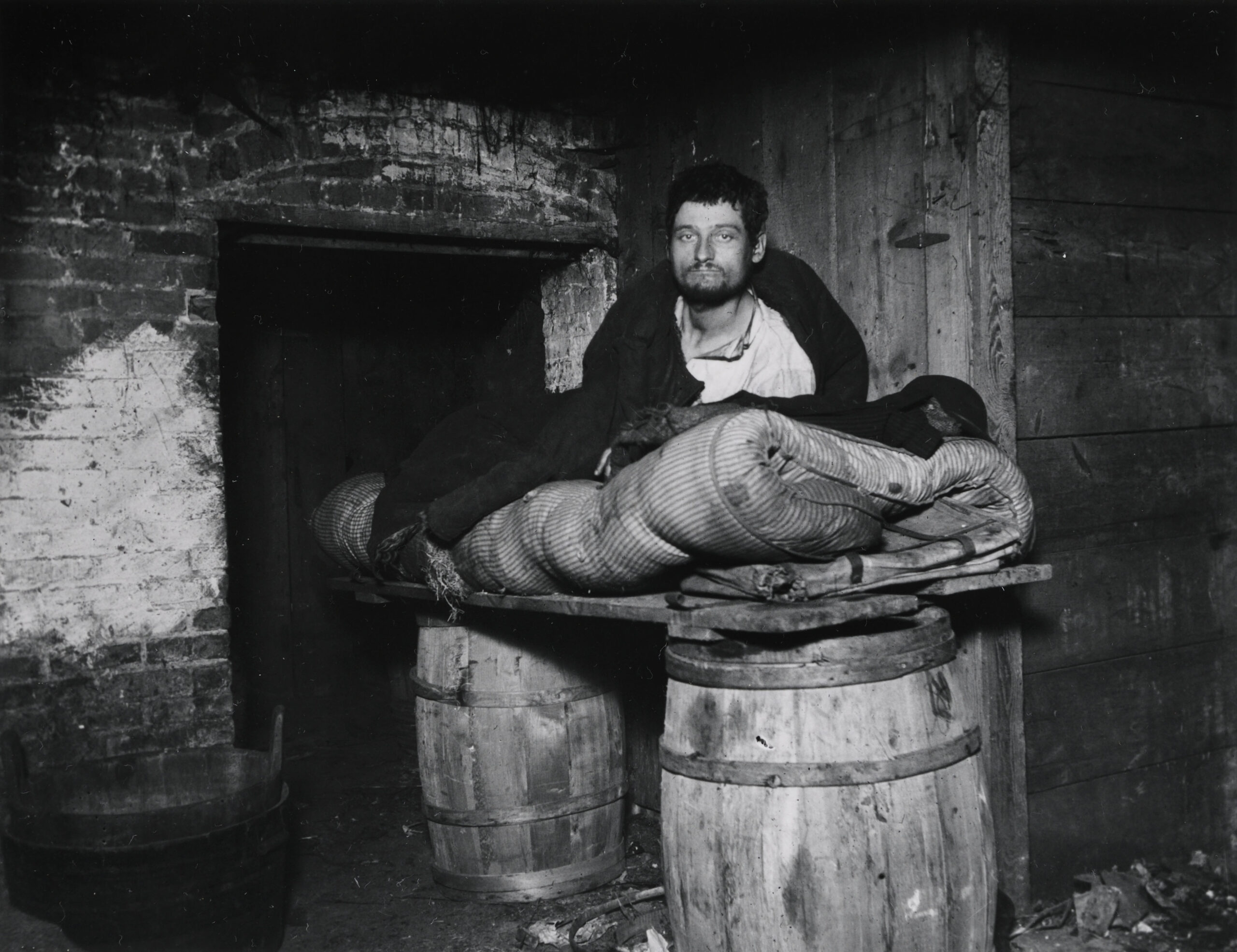

Jacob Riis Riis’ great technical innovation was the utilization of flash powder to penetrate the gloom of tenement apartments, bars, opium dens, and flophouses. Since he was a police reporter, one imagines him arriving with an escort of cops from the downtown Mulberry Street station rapping on doors with their billy clubs and barking orders to open up. Riis and his assistants would bustle about, setting up their glass plate camera, followed by a blinding explosion of light revealing stunned individuals frozen in their nocturnal lairs. Outdoors, Riis clearly orchestrated many of his compositions, undoubtedly positioning people in the frame. One of his most famous images, “Bandits Roost,” has the look of a theatrical set, with a dozen rough-looking figures distributed throughout a narrow alley beneath a cascade of laundry flapping in the breeze. It’s a memorable image. But in general, Riis portrays people as victims rather than individuals who have agency over their own lives.

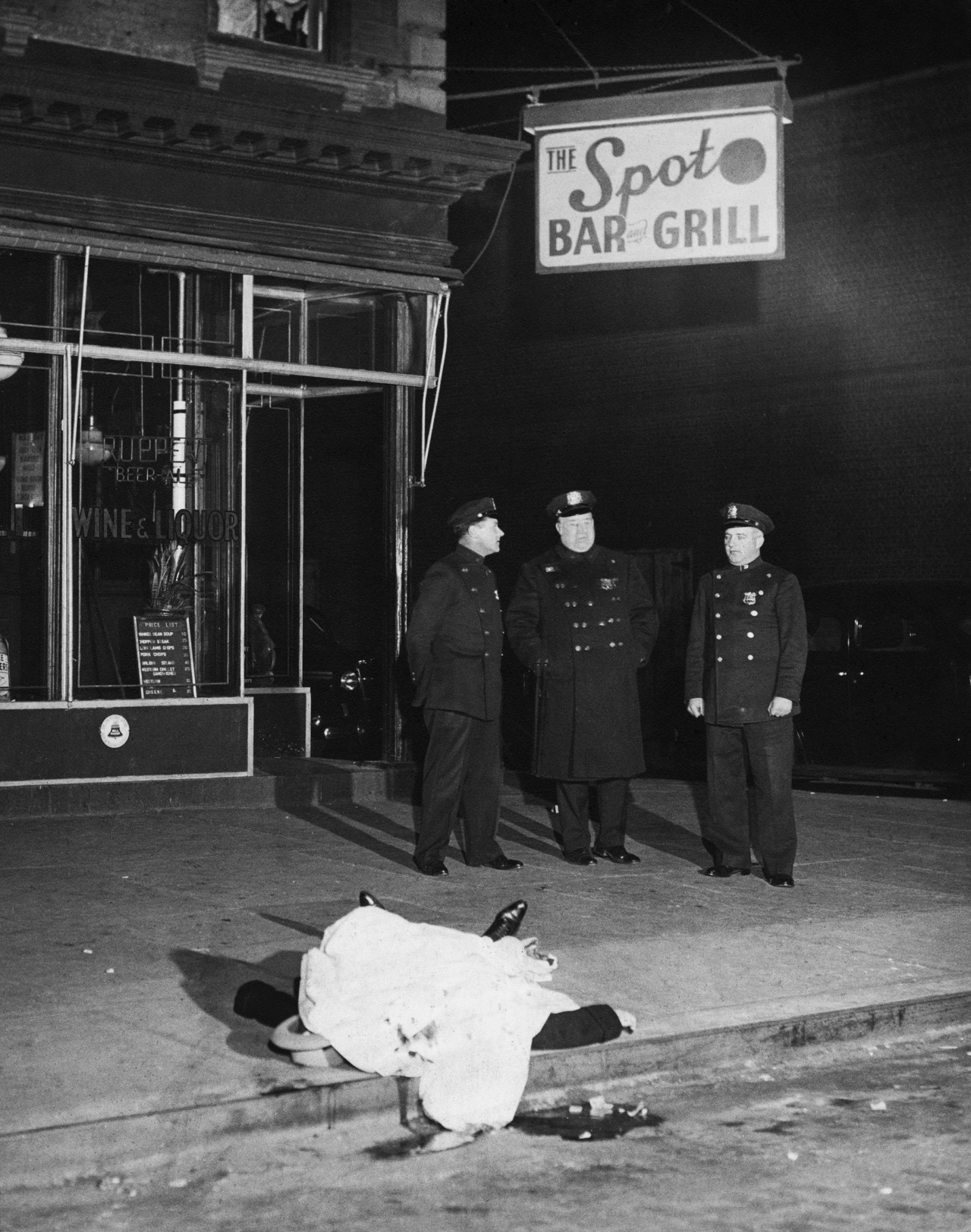

For all of Riis’ concerns about human degradation in the slums, he made callous use of people trapped by circumstances to further his aims. He appeared to have no qualms about invading their spaces, disrupting family lives, and violating personal autonomy. Riis was a showman as well as a reformer – his lectures were intended to entertain – and there is a straight line from his work in the late 19th century to Weegee in the 20th, who was also a press photographer who pursued the denizens of the night with his camera, especially on the Lower East Side. But Weegee was hardly a reformer and understood, first and foremost, that sensationalism sells newspapers. He was a populist carny – but more than exploiting the victims of crime; he exploited us – brilliantly. Riis, in contrast, was a stern and pious scold.

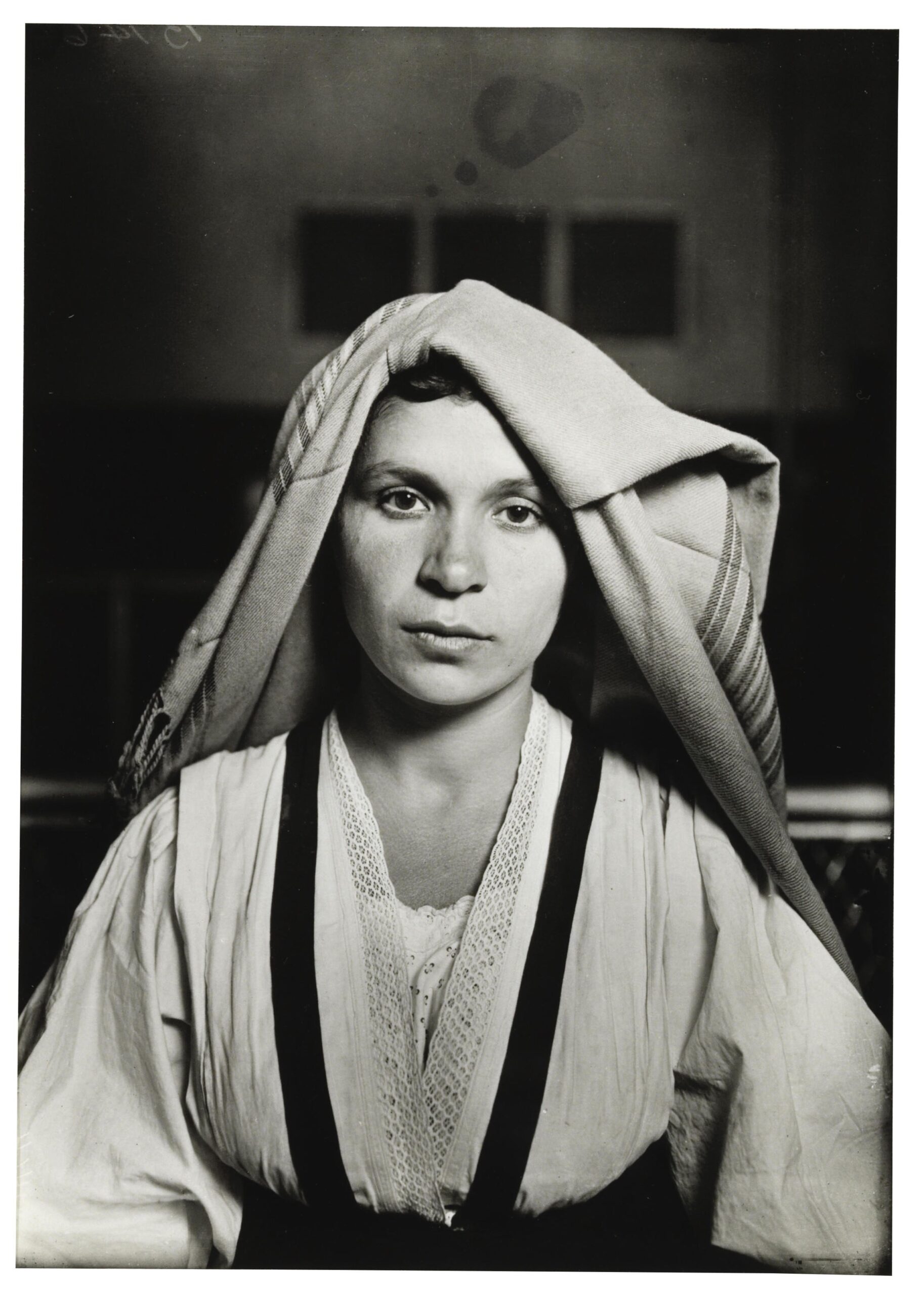

Lewis Hine In my class at ICP, I compare Riis to Lewis Hine, who followed in his footsteps on the Lower East Side and is best known for his photographs documenting child labor. Hine was equally engaged as a social reformer, but his portraits of people do not objectify his subjects the way Riis’ did. Hine’s images of newly arrived immigrants on Ellis Island convey the dignity and vulnerability of individuals fleeing from oppression or simply aspiring to a better life. Instead of Riis’ harsh magnesium flash, Hine was attentive to the glowing light that filtered through the arched windows of Ellis Island’s Great Hall, illuminating faces weary, worried, but hopeful. Many of the people Hine photographed undoubtedly ended up in the tenements that Riis condemned as evil on the Lower East Side, for better or worse. But one suspects that their fates were not always as bleak as depicted in Riis’ photographs.

Weegee Inevitably, in the act of photographing those who are disadvantaged or caught up in circumstances beyond their control, there is an unequal balance between photographer and subject. There is always a hint of exploitation. This is true of both photographers. But In Riis’ case, it is more than a hint. Photographers often deny it, but there is a degree of predation inherent in the act of making pictures. I think Weegee understood it when he said, “…you can’t be a nice nelly and do photography.” But even in warfare, there are certain rules of engagement. In Riis’ war on poverty, his subjects were often treated as nothing more than visual cannon fodder. There are exceptions, however. Riis’ beautiful image of three young women making direct eye contact with the photographer, described as election inspectors, shows what he might have done had he regarded photography as more than a didactic tool.

Jacob Riis So, what do we do with Riis? I still intend to present his work to my class and discuss the issues I’ve touched on here. I think it is important to grapple with the fact that strong imagery and good intentions do not necessarily go hand in hand. Riis’ moral certitude provided him with what he must have considered adequate justification to intrude on others. And out of that sense of entitlement came a body of work that established the practice of documentary photography and photojournalism. Like it or not, we have to deal with it.

Jacob Riis was, to be frank, a self-righteous do-gooder, a Christian evangelist with a deeply racist outlook on those who occupied the crowded polyglot of the Lower East Side. And yet, for years, the consensus has been that he is a heroic figure. His saintly image began with President Theodore Roosevelt, who met and befriended Riis while getting started in New York politics. Roosevelt wrote:

“Recently a man, well qualified to pass judgment, alluded to Mr. Jacob A. Riis as “the most useful citizen of New York.” Those fellow citizens of Mr. Riis who best know his work will be most apt to agree with this statement. The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent ever encountered by them in New York City.”

The Jacob Riis Museum in Ribe, Denmark, his hometown, offers awards to young photographers whose images evoke the “spirit, vision, energy, and passion of Jacob A. Riis who believed photography was one of the most powerful ways to tell a story, provide hope, bring light to darkness, and educate and inspire people.” I’m not sure that Riis was exactly doing any of those things, though passionate he undoubtedly was.

Riis Houses There are parks and schools named for Riis, even a popular beach, and most notably in Manhattan, the Jacob Riis Houses on Avenue D on the Lower East Side, a collection of brick towers that replaced a former tenement and warehouse district along the East River. These buildings, and other projects like them, continue to provide much-needed low-income housing, but they came at the price of indiscriminate slum clearance and the brutal displacement of residents. The Jacob Riis Houses were products of the imagination of Robert Moses, the autocratic master planner who believed in the use of government to remake society. Like Riis, he tended to see people in the abstract rather than as the lifeblood of the city. Ironically, due to design principles inspired, in part, by the imperative for light and air – espoused by Riis and his followers – these monoliths on the East River have become symbols of low income housing gone awry.

So, I have an issue with Jacob Riis. It’s time we consider his legacy fully with all its contradictions and set the record straight. He was an important but highly problematic figure both as a social activist and as a photographer. And maybe – I haven’t made up my mind – it’s time to consider renaming those buildings on Avenue D.

Brian Rose

-

Iron Curtain, 1985/87

Near Ratzeburg, Germany, 1985 – © Brian Rose It has been suggested that I might have been paying homage to Andreas Gursky in one of my photographs of the Iron Curtain border from 1985. I don’t believe I was familiar with his work at the time, but certainly, I was aware of images by earlier color photographers like Shore and Meyerowitz, and subsequently, Sternfeld.

The so-called Düsseldorf school of photography was not really on my radar until later. You have to remember, of course, that there was no internet in 1985, and art photography was still not widely published. I was fortunate, however, living in New York, to see lots of exhibitions in both museums and private galleries.

Oebisfelde, Germany, 1987 – © Brian Rose There were a number of influences that came into play when I began photographing the east/west border in Europe. One of them was Anselm Kiefer whose paintings were first exhibited in New York in 1982. There was one painting in particular, “Nürnberg,” a large landscape showing a field embedded with actual straw, and the skyline of the city in the distance

Nürnberg by Anselm Kiefer, 1982 I don’t know whether I saw Kiefer’s painting before or after I made my photograph of Oebisfelde with its snow-crusted furrows and the distant line of the border wall, guard tower, and church spires. But his landscape work, in general, which evokes the dark history of Central Europe, haunted me throughout my project.

-

Kröller-Müller Museum, The Netherlands

Aldo van Eyck Pavilion, Kröller-Müller Museum, The Netherlands – © Brian Rose The Aldo van Eyck pavilion at the far end of the Kröller-Müller sculpture garden is well worth seeking out. It is actually a reconstruction of a temporary exhibition space for sculpture built in 1966. Van Eyck is not well-known in the United States, but his influence as an architect and theorist extends well beyond the Netherlands.

As I was walking around the pavilion I was struck by its similarity to Louis Kahn’s bath house in Trenton, New Jersey. The cinder block material, the way in which the roof was suspended above the walls, and the juxtaposition of geometric forms, all reminded me of Kahn’s temple of utilitarian changing rooms and showers. I photographed it some years ago before and after its restoration.

Louis Kahn Bath House, Trenton, New Jersey – © Brian Rose It turns out that the two architects met here at the Kröller-Müller in 1959. Robert McCarter, architect and professor writes in a 2018 essay: “The paths of these two architects – the Second-Generation modernist Kahn, then 58 years old, and the Third-Generation modernist Van Eyck, then 40 years old – parallel in so astonishingly many ways, crossed here for the first time, deeply affecting them both at a time of critical transition in their respective practices and thought.”

https://krollermuller.nl/en/aldo-van-eyck-aldo-van-eyck-pavilion

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6865075.pdf (PDF) -

Southampton County, Virginia

Southampton County, Virginia, 2024 – © Brian Rose There is no Nat Turner memorial in Southampton County. No museum or documentation center. There are only fragments of buildings, and Turner’s sword remains under lock and key in the county courthouse. Primarily, there is the landscape, largely frozen in time, as memorial in itself. How do you photograph that which is missing? How do you fill in the gaps in the story? In the picture above, somewhere along the trail of Turner’s path of righteous destruction, a grove of mature trees marks the location where a farmhouse once stood. Sometimes absence and presence blend into one another, and the past and present conjoin and occupy the same ground.

-

Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg, Virginia – © Brian Rose

I grew up in Williamsburg, Virginia, and as a result, was steeped in American history. I was a member of the Colonial Williamsburg Fifes and Drums, and with the corps, played for two U.S. presidents and many other heads of state and dignitaries.

Colonial Williamsburg, from the beginning, told an idealized, and sanitized, version of American history. The triumph of liberty over tyranny. The restored houses and reconstructions were of clean white clapboard. The decorative gardens and tidy rear kitchens suggested an orderly and civilized society. The presence of slave labor was not dwelled upon, though acknowledged as a temporary evil eventually to be done away with. Jefferson, Washington, and Patrick Henry were portrayed as heroes who not only stood up to a despot, but inspired the creation of a new nation, democratic and egalitarian. The founding fathers were towering figures.

They were – but we see them now through less rosy glasses, and in recent decades, the foundation has made much progress in telling the full narrative. The enslaved are now included as integral to the 18th century colonial capital, and recently, CW commemorated the restoration of the Bray School, a building from 1760 that was dedicated to the education of black children. The Colonial Williamsburg website states without mincing words that: “the school’s faith-based curriculum justified slavery and encouraged those who were enslaved to accept their destinies.”

Whatever its shortcomings, the central mission of Colonial Williamsburg remains “”That the future may learn from the past.”

We have just elected a president who is a repudiation of the ideals of Jefferson and Washington. A vulgar disreputable criminal. A rapist. A man with no character and no moral compass, and certainly, no sense of history to learn from. Will Colonial Williamsburg survive this debauchery of American history. Will the Republic survive?

-

Talkin’ Greenwich Village by David Browne

I just finished reading David Browne’s meticulously researched four-decade history of the Greenwich Village music scene. In my other life, I was part of this world – a fledgling songwriter, co-founder of the Fast Folk Musical Magazine, and occasional photographer of my musician friends. Although my role in Browne’s narrative does not quite reach the centrality that it does in the imaginary movie of myself, I am mentioned several times in the book and cannot complain. I also contributed a photograph taken in front of Folk City in 1981.

From left to right: Lucy Kaplansky, Rod MacDonald, Gerry Devine, Martha P. Hogan, David Massengill, Tom Intondi, Jack Hardy, and Bill Bachman. Photo © Brian Rose Having been intimately involved with many of the events and people depicted in the book, I can attest to its remarkable accuracy. Browne, a senior writer with Rolling Stone, has attempted a definitive history here, which is pretty ambitious, and he weaves together many different threads with skill. There are several main characters in the story, but the most important is Dave Van Ronk, whose influential presence and career, spans almost the entire timeline of the book. A difficult task was including the mostly parallel Village jazz scene with innovators like Miles Davis and John Coltrane alongside the folk scene with songwriters like Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs. I understand why Browne did it, but sticking to the folk music scene might have made for a less complex narrative structure.

One of my favorite parts of the book is a delirious description of the 1975 birthday party for Folk City owner Mike Porco.

“For the expanding crowd inside, the evening grew only more Fellini-esque, with a mélange of folk, spoken word, and cabaret moments that recalled an earlier, headier time in the Village—a grown-up version of the old Gaslight. Patti Smith improvised a poem. Ginsberg recited from William Blake. Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, who’d become part of the Other End hang-out crew, materialized to play “Chestnut Mare” and “I’m So Restless,” the latter with its sly dig at Dylan’s semi-retirement. Bette Midler, who’d also befriended Dylan, sashayed toward the stage and joined Buzzy Linhart on his song “Friends,” which had become an anthem for her.”

Browne, David. Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital (p. 242). Hachette Books. Kindle Edition.

-

Coney Island

Lower income housing north of the elevated subway line in Coney Island. 6sqft:

“After World War II, Coney Island’s popularity began to fade, especially when Robert Moses made it his personal mission to replace the resort area’s amusements with low-income, high-rise residential developments. But ultimately, it was Fred Trump, Donald’s father, who sealed Steeplechase’s fate, going so far as to throw a demolition party when he razed the site in 1966 before it could receive landmark status.”

Trump invited guests to the demo party to throw bricks through the glass facade with its iconic grinning face. Fred also had plans to develop the former Luna Park site, but could not acquire government financing because he and his son were sued by the U.S. Government for racial descrimination. Instead, Robert Moses erected his customary forest of low income towers just north of the elevated subway line across the street from the amusement park.

“This sad event,” Charles Denson, the executive director of the Coney Island History Project, wrote in conjunction with the exhibition’s debut last summer, “was a vindictive and shameful act by a grown man behaving like a juvenile delinquent. It wasn’t business—it was personal. The desecration of an icon and the breaking of glass as public spectacle revealed a twisted personality that was unusual for even the most hard-bitten developers.”

“It’s almost the equivalent of ISIS tearing down religious icons, because the Steeplechase face was so iconic and really represented Coney Island,” Denson told me Saturday.

“Horrifying,” he called what Fred Trump did.

“Barbaric,” said Tricia Vita, the administrative director of the History Project.

The grinning funny face of Steeplechase Park lives on as the de facto logo of Coney Island. -

Nat Turner’s Sword

After much research and soul searching, I made an exploratory journey to Southampton County in southern Virginia. A deep dive into the darkest heart of America. I am on my way to Courtland, Virginia to tour the route of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion of 1831. My hotel just off I-95 is next to a truck stop with fast food and, thankfully, a Starbucks. Down the road that parallels the freeway, the Blue Star Highway, I found Los Compadres Mexican. The crowd was Trumpy looking – one man had a sweatshirt emblazoned with “Virginia is for Hunters” – but the vibe was good, the food spectacular, and the Mexican restaurant staff, apparently, on friendly terms with the locals.

Stony Creek, Virginia, 2014 – © Brian Rose

Rick Francis, the county clerk, led the tour that followed the route of Nat Turner’s murderous rampage through the countryside of Southampton County, the biggest slave revolt in American history. We traveled together by bus, a group of both whites and blacks, some locals and some who drove in from miles away, like me. Some had family connections to the people of 1831 when the uprising took place, but few were as close as mine. More on that later.

Cross Keys, Southampton County – © Brian Rose I was thirty-one years of age the 2nd of October last, and born the property of Benj. Turner, of this county. In my childhood a circumstance occurred which made an indelible impression on my mind, and laid the ground work of that enthusiasm, which has terminated so fatally to many, both white and black, and for which I am about to atone at the gallows. It is here necessary to relate this circumstance–trifling as it may seem, it was the commencement of that belief which has grown with time, and even now, sir, in this dungeon, helpless and forsaken as I am, I cannot divest myself of.

A steady soaking rain kept us in the bus most of the day, but I jumped out here and there and made pictures mostly from the road. There aren’t many structures still standing from 1831, but the landscape remains relatively unchanged and relatively undeveloped. This is Cross Keys, at the center of Turner’s meandering path across the countryside. It was not a town – there were none in those days – save for Jerusalem, the county seat about eight miles away.

Richard Porter house, Southampton County – © Brian Rose This is what is left of the Richard Porter house, where a young enslaved girl warned the family of Turner’s approaching band, and they were able to escape into the nearby woods. The chimney is visible at the center, while two vultures perch on the branches at the upper right. I came back the next day and photographed the ruin from a different angle. Across the road, behind an abandoned shack, I found the graves of Richard Porter and his wife.

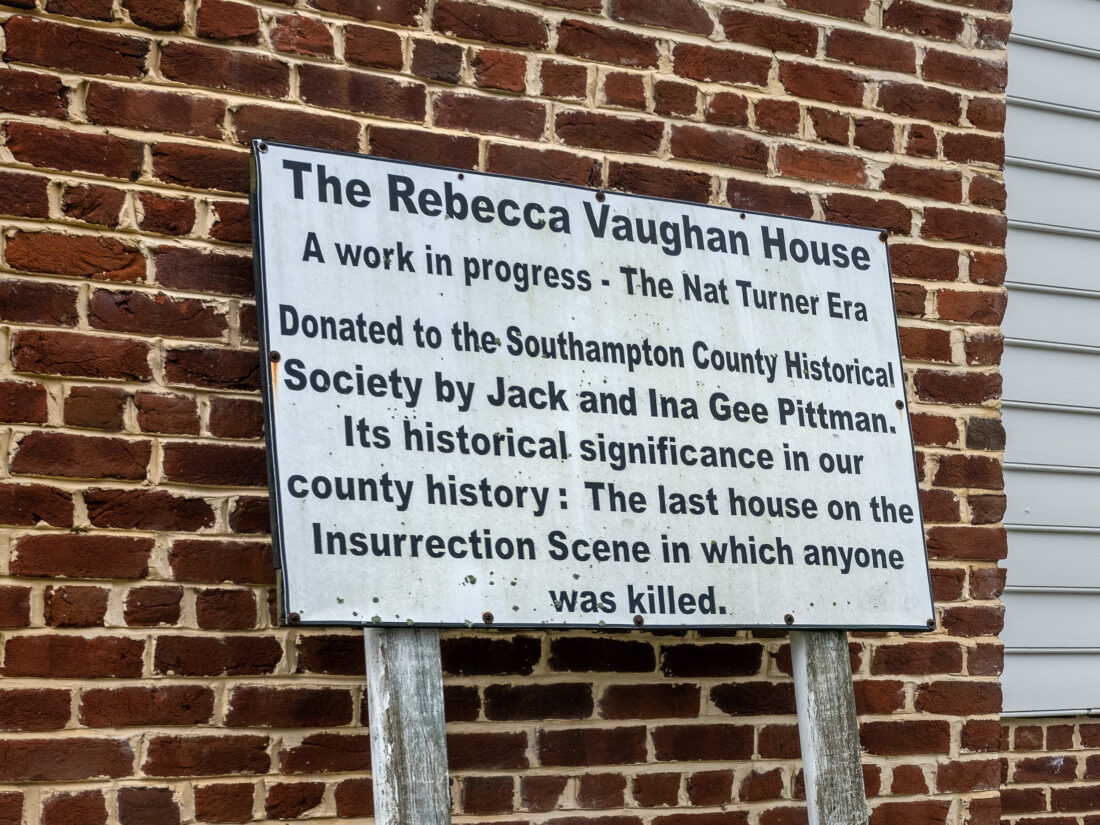

Richard Porter and Eliza Porter gravestones – © Brian Rose My connection to the story of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion – one of my connections I should say – concerns this small house. Rebecca Vaughan, one of the victims of Turner’s rampage through the Virginia countryside, is my 3rd cousin six times removed. The house once stood abandoned in a field several miles from Courtland, previously called Jerusalem. The current property owner donated the house to the local historical society and it now sits awkwardly behind the now-closed Museum of Southampton History. It has been restored to a pristine condition, which seems, somehow, to hit a wrong note.

Rebecca Vaughan House, Courtland – © Brian Rose

Mrs. Vaughan was the next place we visited—and after murdering the family here, I determined on starting for Jerusalem—Our number amounted now to fifty or sixty, all mounted and armed with guns, axes, swords and clubs… – Confessions of Nat Turner

Rebecca Vaughan House – © Brian Rose

A sign leaned up against one of the chimneys of the Vaughan House. “Its historical significance in our county history: The last house on the Insurrection Scene in which anyone was killed.”In 1831, Nat Turner, an enslaved man, was well-known by many in the county, black and white, for his religious preaching. He was literate in a rural community where many were not. He claimed to have visions and was called upon to lead an uprising against the slaveholders of Southampton County. They would gather reinforcements as they moved from farm to farm. Their goal was the county seat of Jerusalem. In an area where blacks outnumbered whites 3 to 2, success seemed plausible, if not, in the end, practical. The core group of Turner’s band met here at Cabin Pond at two in the morning and then struck the nearby Travis farm where Turner was enslaved.

Cabin Pond – © Brian Rose Although few structures remain from 1831, when Nat Turner led his compatriots in a rampage against the slaveholders of Southampton County, the locations of the various farms are known. Whether freedom fighters or terrorists, their methods were brutal, and the relatiation by Whites was equally brutal. When Turner was in jail awaiting trial, he recounted the grisly details of his rebellion to Thomas Gray, a lawyer. Gray may have sensationalized the telling, but the facts remain undisputed.

Hark got a ladder and set it against the chimney, on which I ascended, and hoisting a window, entered and came down stairs, unbarred the door, and removed the guns from their places. It was then observed that I must spill the first blood. On which, armed with a hatchet, and accompanied by Will, I entered my master’s chamber, it being dark, I could not give a death blow, the hatchet glanced from his head, he sprang from the bed and called his wife, it was his last word, Will laid him dead, with a blow of his axe, and Mrs. Travis shared the same fate, as she lay in bed. – Confessions of Nat Turner

Travis Plantation – © Brian Rose

Blackhead Signpost Road – © Brian Rose BLACKHEAD SIGNPOST ROAD

In Aug. 1831, following the revolt led by enslaved preacher Nat Turner, white residents and militias retaliated by murdering an indeterminable number of African Americans – some involved in the revolt, some not – in southamnpton County and elsewhere. At this intersection, where Turner’s force had turned toward Jerusalem (now Courtland), the severed head of a black man was displayed on a post and left to decay to terroize others and deter future uprisings against slavery. The beheaded man may have been Alfred, an enslaved blacksmith who, though not implicated in any revolt killings, was slain by militia near here. The name of this road was changed from Blackhead Signpost to Signpost in 2021.

Capron, Southampton County – © Brian Rose

Capron, Southampton County – © Brian Rose

Capron, Southampton County – © Brian Rose I was told about an artist in Capron who painted scenes relating to the Nat Turner insurrection. I took a few pictures along the main street of the town including this one of the abandoned passenger train station. Behind me a few doors down I saw someone in his front yard and asked if he knew of a well-known artist in Capron. He said he lives right here next door. I did something I rarely do, I walked straight up and knocked on his door.

Mr. James Magee ushered me into his parlor and called for his wife and daughter to sit with us. He was a tall, thin, Black man – 94 years old – with a soft Virginia accent, and he asked why I had come, and how I had found him. We talked for about a half hour. He was disdainful of the tour I had taken retracing the path of Nat Turner and his compatriots, but eager to engage in conversation. He then showed me around his house full of antiques, two rooms of books, African-inspired art, his studio, and his paintings – large realistic paintings of historical events. They were painted with an astonishing vigor, powerful, disturbing, but beautiful.

Unknown title by James McGee He made it clear from the moment I sat down that I was not to photograph anything. The image above, greatly enlarged, was the only one I could find on the internet. None of his paintings have been sold. None are in public collections. McGee said his wife and daughter would take care of his legacy. I told him about my relationship to Rebecca Vaughan, one of Turner’s victims. 3rd cousin six times removed sounds close I said, or not so close. Whatever the case, Rick Francis told me on the tour bus that I was the closest relative to Vaughan he had yet encountered.

McGee was not convinced that the Southampton County Historic Society had the real Rebecca Vaughan house, but I couldn’t see any reason why they would make something up like that. It was evident that McGee was beginning to wrap up our visit. He told me that he would show me the upstairs of his house when I made my next visit, which I took as an invitation to return. He then reached for the knob of a battered door that was hinged to the wall but did not open or close on an actual doorway. It merely swung on the wall. McGee looked at me with a penetrating stare and exclaimed dramatically, “This is the door of the Rebecca Vaughan house!

Southampton County – © Brian Rose I ran away from Virginia when I was 20 or so with dreams of making it in New York. But I wasn’t fleeing the state as much as I was trying to free myself from a sense of darkness that cloaked my family’s past, a past that was essentially a black hole. No grandparents on either side of the family. They had died young, at least on my father’s side. My mother did actually run away when she was 16, and as a result, I had no contact with her side of the family. As I grew older I lost contact with most of my relatives, and those that I knew began to die off. I remained haunted, however, by the landscape of Isle of Wight and Southampton Counties – the southside of the James River – a mental and physical topography both alien and familiar.

Down Below the James – © Brian Rose In New York, I made photographs and wrote songs, splitting my time as best I could between two demanding pursuits. One day a song emerged effortlessly as if from the ether. “I spoke my name out loud/It floated like a cloud/not knowing that I was freed/I quivered like a reed/whispering my name/down below the James.” I was, it seems, expressing a desire for liberation from an unseen past, but I also knew instinctively that this was a song about slavery and the sins of my ancestors. “What smoke-thin ghost is wont, among these tin roof haunts, endless trains of coal, pass by the old swimming hole, my history and shame, down below the James.” It was the first song I ever recorded and appeared in the Fast Folk Musical Magazine in 1981.

Despite this bolt out of the blue that hinted, unconsciously, a connection to the infamous Nat Turner insurrection, I did not pursue it, and in those days, there were few ways to trace family history short of going to local courthouses and libraries and doing painstaking research. I was familiar with the Turner story having read William Styron’s “Confessions of Nat Turner” when in high school. The book made a lasting impression on me, and I related to Styron himself, who had left Virginia for New York City and a literary career. Moreover, I was aware that my uncle’s hog trucking business was located in Courtland, Virginia, the Southampton County seat, and originally called Jerusalem. Capturing Jerusalem was undoubtedly the proximate goal of Nat Turner as he led his band of rebels from farm to farm across the county. My father, who never said much about his upbringing in Walters, Virginia – located about 15 miles from Courtland – but he told me once that he remembers as a child waking one night to the terrifying sight of a cross aflame in the yard of his house. He could not explain why or whether the Roses were being targeted by the KKK. It remains a mystery.

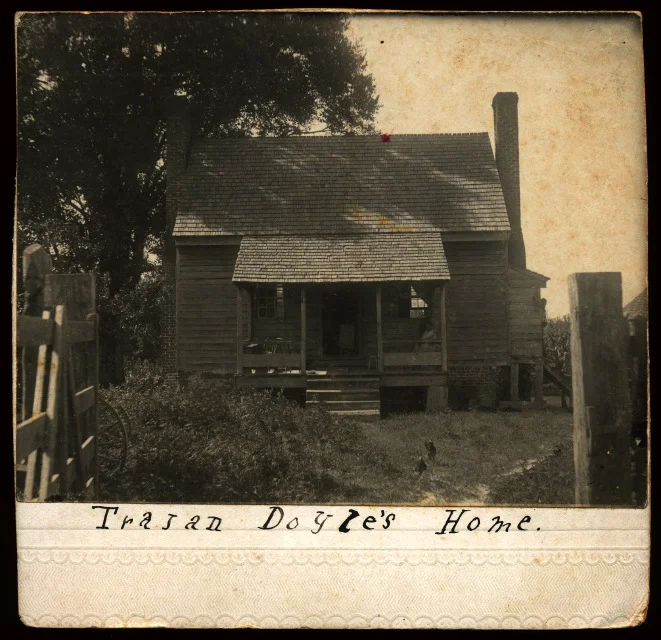

Trajan Doyle house taken by William Sidney Drewry During the Covid pandemic of 2020 I began researching my family roots online. I quickly discovered that my mother’s side of the family had come to Virginia from Mississippi and that my great, great, great, grandfather had been killed in the Battle of Vicksburg fighting on the side of the South. On my father’s side, however, the trail back in time was more difficult, as the genealogy work done by others only took me so far. So, I began the slow process of tracking down documents and making connections on my own. A few generations back, I followed the trail to the Doyals of Southampton County. My 3rd great-grandfather was Richard Doyal.

We again divided, part going to Mr. Richard Porter’s, and from thence to Nathaniel Francis’, the others to Mr. Howell Harris’, and Mr. T. Doyles. On my reaching Mr. Porter’s, he had escaped with his family. I understood there, that the alarm had already spread, and I immediately returned to bring up those sent to Mr. Doyles, and Mr. Howell Harris’; the party I left going on to Mr. Francis’, having told them I would join them in that neighborhood. I met these sent to Mr. Doyles’ and Mr. Harris’ returning, having met Mr. Doyle on the road and killed him…

-

Amsterdam

Herengracht, Amsterdam – © Brian Rose This is central Amsterdam, the canal belt, “grachtengordel” in Dutch, still functional despite the intimacy of the streets and architecture. Fashionable (gentrified), full of shops, people on foot, on bikes, and a Tesla quietly slithering through. The composition echoes the great Gustave Caillebotte street scene of Paris in the Art Institute of Chicago. Paris is, of course, different in scale, and the painting achieves a geometric orderliness that the photo does not. But both images convey a simultaneous sense of modernity and timelessness.

Paris Street, Rainy Day – Gustave Caillebotte -

Jamaica Estates / Queens

At the end of the F train, I made my way a few blocks north to the boyhood home of Donald Trump, former president of the United States. On a street lined with tidy Tudor bungalows, the yard in front was choked with weeds, and a sign said, “Do not remove kittens from the property.” A cat with piercing green eyes sat next to the mailbox, red flag up. As I walked away, the cat followed, and stayed with me for several blocks, disappearing, and then popping up again in front of me. -

New York – Eighth Avenue

This is an image from my ongoing series “Last Stop,” documenting the neighborhoods at the ends of all the subways lines in New York City. While many of the lines terminate in far-flung extremities of the city, a number of them end in Manhattan, like this one, the last stop of the L train at Eighth Avenue near the Meatpacking District.

One of the basic facts of life when photographing New York is the ubiquitous, and powerful, presence of the street grid. You fight it at your peril as you chase down the sunlight between the tenements and towers.If I never have a cent

I’ll be rich as Rockefeller

Gold dust at my feet

On the sunny side of the street

– Dorothy Fields

The streets of Manhattan are famously straight, and they all recede to the horizon in forced monotony, a tyranny of perspective that must be accepted. Resistance is futile, though one looks for breaks in the street wall, or takes refuge in parks that are few and far between. But there is always action on the corner where streets converge, where pedestrians intermingle and collide, where right angles interrupt the flatness of facades, and the world comes alive in three dimensions.

And the poets down here don’t write nothing at all

They just stand back and let it all be

– Bruce Springsteen

The L train from Brooklyn ends at Eighth Avenue where it intersects with the A, E, and C trains coming down from Harlem stretching out all the way to the beaches of the Rockaways. A dignified neo classical bank building now houses a CVS pharmacy with its slapdash red logo adorning a richly sculpted bronze clock beneath a beehive, a symbol of thrift, as industrious bees buzz around the clockface and pigeons perch above.I’m shining like a new dime

The downtown trains are full

With all those Brooklyn girls

They try so hard to break out of their little worlds

– Tom WaitsI stood on the curb of a protected a bike lane, and centered my shot on the clock just above the subway entrance, and locked the composition onto the pilasters and columns of the bank. I made sure the poles supporting the traffic lights stood free of these architectural elements and pointed the camera slightly to the left to include the subway elevator structure. The stage set, I waited for the actors to emerge from the wings.

Now the curtain opens on a portrait of today

And the streets are paved with passer-by

And pigeons fly, and papers lie

Waiting to blow away

– Joni Mitchell

Secondarily, I was aware of the gaggle of people behind. A boy in blue with red shoes stopped briefly, a tall thin man separated from the crowd, and I could see that people were arrayed evenly across the frame. You have to trust your instincts. There is no time to analyze or second guess. Everything falls into place, as if you are in control, and chaos is ordered and tamed.Don’t ever change, don’t ever worry

Because I’m coming back home tomorrow

To 14th Street

Where I won’t hurry

And where I’ll learn how to save

Not just borrow

– Rufus Wainwright

I saw the couple approaching arm-in-arm, an elderly woman in an overly long trench coat and someone younger, perhaps her daughter in a puffy winter jacket. They moved briskly toward the corner and the crowd swirled around them as if they were meant to be the focus of the scene. I made four frames concluding with the couple entering the crosswalk, the older woman gripping her cane tightly peering ahead over her reading glasses halfway down her nose. They held each other closely, striding forward, the daughter raised her hand to her face as if reacting to something her mother said.

It was a cloudy day when I took this picture. No shadows, no sharply slanted November light, no sunny side of the street. Every detail was equal like the composition itself, a multiplicity of visual anecdotes played out on an architectural set. The mother and daughter moving through and out of the frame, the elegantly poised man at center beneath the clock, the boy in red shoes who appears to be hamming for the camera (but is not), the blue jacketed man glancing at his phone, the woman carrying something fuzzy – maybe a dog – the people facing left waiting for the light to change, the transit worker in uniform lost in thought, the bottle and can scavenger bent over his double-wide baby stroller, stolen or found, who knows. No one notices that I am standing directly in front of them, like a conductor before an orchestra, except for one man off to the right who looks directly at me.We are all participants in this scene, in the dynamic of urban drama played out on the street. But were everyone to walk away, were the human figures to be erased, the urban landscape and architecture would remain, which is where this photograph begins and ends.

A concrete jungle where dreams are made of

There’s nothing you can’t do.

Now you’re in New York

These streets will make you feel brand new

Big lights will inspire you.

– Jay-Z